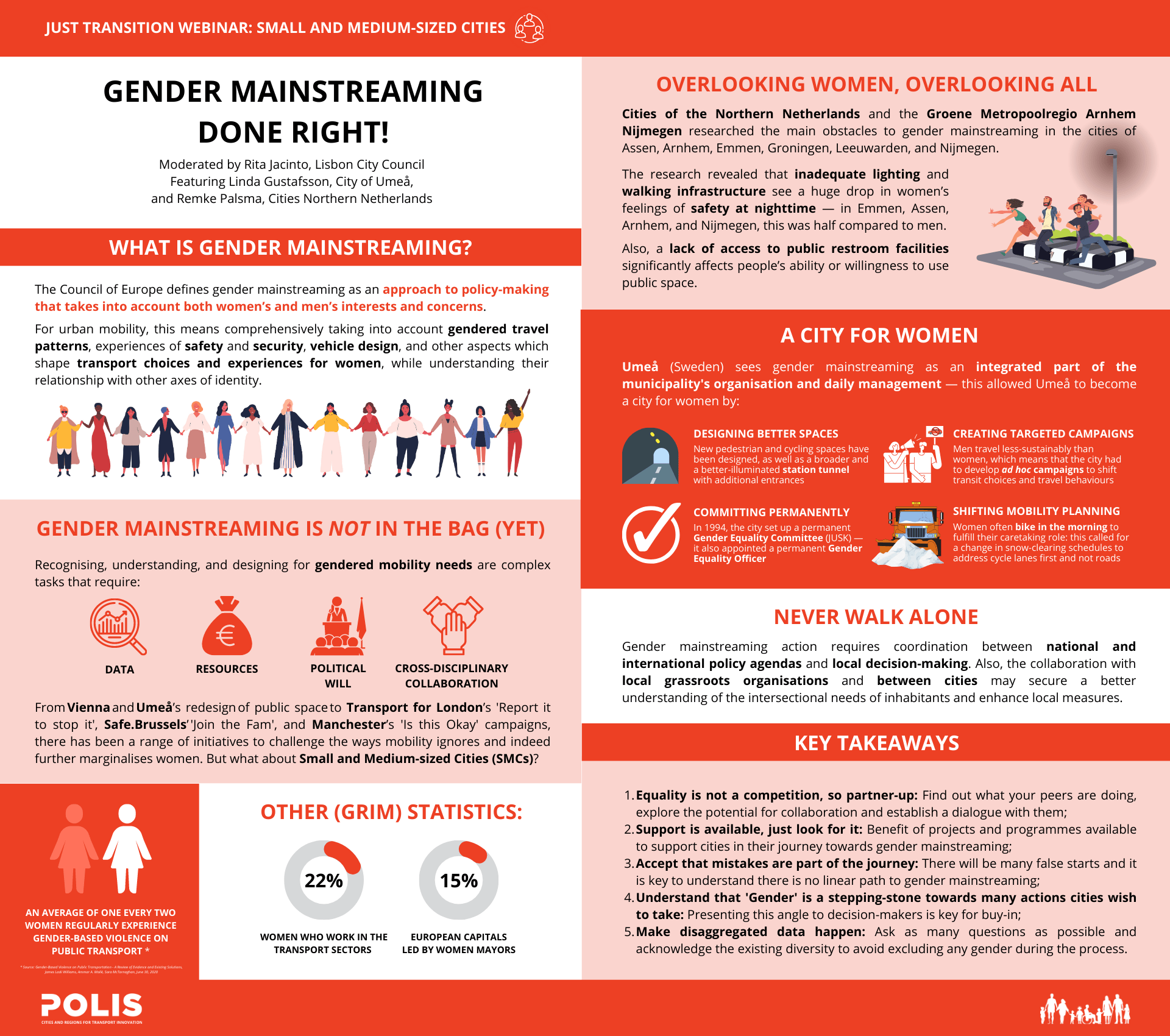

SMCs Just Transition Webinar: Gender equity comes in… small packages?

POLIS' Just Transition Webinar brought together leading gender experts from across Europe to discuss how small and medium-sized cities are mainstreaming gender-equal mobility, the challenges they have faced, and lessons for others.

Recognising, understanding, and designing for gendered mobility needs is a complex task; it demands data, resources, political will and cross-disciplinary collaboration. While we have seen much progress over the last decade, gender mainstreaming is far from, “in the bag”.

From Vienna and Umeå’s redesign of public space to Transport for London’s ‘Report it to stop it’, Safe.Brussels’ ‘Join the Fam’, and Manchester’s “Is this Okay” campaigns, there has been a range of initiatives to identify and challenge the ways mobility ignores — and indeed further marginalises —women.

While these actions in European capitals capture headlines, it is in fact in our small and medium-sized cities (SMCs) where some of the most pioneering strategies are to be found. These are often cities using resources in innovative ways, creating new avenues for collaboration, and pushing beyond the “vulnerable user” paradigm to support women as transport users, and decision-makers.

Our SMCs are proving small, but mighty! Exploring research from cities of the Northern Netherlands and insights from projects on the ground in Umea, POLIS’ Just Transition webinar looked at what our smaller cities may be able to teach others in the field about the future of gender mainstreaming in urban mobility.

What is gender mainstreaming?

The Council of Europe defines gender mainstreaming as an approach to policy-making that takes into account both women’s and men’s interests and concerns. The concept of gender mainstreaming was first introduced at the 1985 Nairobi World Conference on Women.

It is about finding the inherent differences between men and women through data collection and taking them into account when creating, implementing and evaluating policies, as to foster gender equality. For urban mobility, this means comprehensively taking into account gendered travel patterns, experiences of safety and security, vehicle design, and other aspects which shape transport choices and experiences for women, while understanding their relationship with other axes of identity.

While many definitions do not include the importance of understanding gender fluidity, this aspect emerged as key in this webinar — there is clearly much work to be done here!

Image: Challenges being encountered by decision-makers and practitioners across the transport sector, exchanged on the MiroBoard during the webinar

The story so far: Improvement… but a long way to go

The transport sector has seen a growing focus on gendered mobility patterns and bolder efforts to combat inequity at the international, national, local, and organisational levels. The European Commission’s Women in Transport platform, Ambassador for Diversity initiative and European Charter for Equality of Women and Men in Local Life, have placed gender higher than ever on the international stage, while cities and operators such as EMT Madrid, SBB, London Councils and Transport for London have radically reorientated their policies and practices to ensure gender perspectives are integrated into services and operations, and a far greater diversity of voices are driving decision making.

Nonetheless, there is no room for complacency. With copious research still identifying gender-based violence as a regular experience on public transport, women still accounting for just 20% of the transport sector, and under a quarter of European capitals led by women mayors, extensive work is still required.

Mobility is a conduit to economic and political participation, a key tool to cementing equal access to employment, education and healthcare. With global gender equality figures revealing alarming stagnation in progress towards gender equity across these indicators- mobility must step up to the plate.

“Small and medium-sized cities play a very important role in designing and implementing gender-equal mobility, not just in the city, but in the surrounding region,” said Remke Palsma.

“SMCs also show how we can better understand how to prioritise service provision, and deploy resources.”

Northern Netherlands strikes out!

Designing, developing, and delivering gender-sensitive infrastructure requires a deliberative approach; understanding the key issues at play, identifying existing deficiencies, and determining the immediate and longer-term actions available.

This has been the approach taken by the Cities of the Northern Netherlands and the Groene Metropoolregio Arnhem Nijmegen, who, together, commissioned research into the main obstacles for gender mainstreaming in their cities, and the tailored solutions which may be on hand.

“This research sought to assist both entities by supporting them in determining more effective and impactful infrastructure where needs from both men and women are being considered. It also examined the progress in other cities across Europe, and what smaller cities could draw from these,” said Remke Palsma, EU Project Advisor, Cities Northern Netherlands, and co-chair of POLIS’ SMC Platform.

Image: Graphs displaying feelings of safety in several cities in the Netherlands, collected in research conducted for Cities of the Northern Netherlands.

Putting gender equity at the heart of urban planning

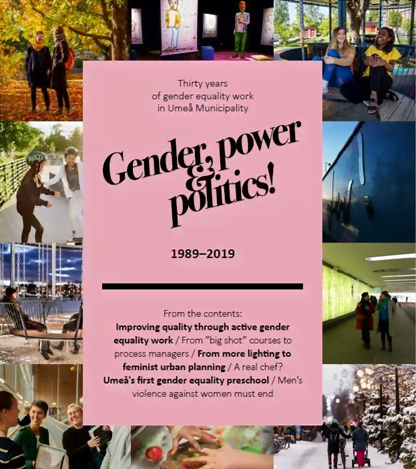

Indeed, this has been the case in Umea, where gender equality work became a permanent and integrated part of the municipality's organisation and daily management, propelled by the Committee on Gender Equality and the position of a gender equality officer.

Umeå has a head start when it comes to redesigning cities for women: since 1978, a gender equality committee has weighed in on the city administration’s policies from a gender perspective. In 1994 Umeå city council launched the Gender equality committee (JUSK), and over 10 years ago it published its first ”Gendered landscape” report, with subsequent regular revisions.

The ways they have designed new pedestrian and cycle spaces. The new tunnel is broader and lighter, with the optimal inflow of light at all entrances and using artificial lights that emulate daylight. Adding entrance in the middle or rounding corners are other examples of how the tunnel has been planned about the feeling of safety in a place that can sometimes be perceived as unsafe.

Critically, by collecting gender-disaggregated data on transport use and perceptions, Umeå identified that men and women travel differently and that men (on average) travel less sustainably- allowing the city to create more targeted campaigns for shifting transit choices and travel behaviours. The data also allowed the city to shift mobility planning to create more gender-equal processes.

For example, this data revealed that women were often the first to use the roads in the morning due to outsized responsibility for caretaking roles, often on bikes. The council, therefore, changed snow-clearing schedules to address cycle lanes first- rather than roads.

“Gender mainstreaming has been a key approach in understanding which actions we need to prioritise, and which actions will support both women and men in making more sustainable choices,” said Gustafsson.

Image: New publication about gender equality work in Umeå, Source: Umea Kommune, New publication about gender equality work in Umeå.

Never walk alone: International action and local cooperation

Gender mainstreaming action demands coordination between national and international policy agendas and local decision-making.

Cities are undoubtedly critical in cementing action on the ground, and particularly smaller cities have proved incredibly effective in taking swift and targeted action on many aspects of sustainable urban mobility- it is no coincidence that many SMCs have been selected for the EU’s Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission.

Faced with limited resources, SMCs have proved particularly adept at finding innovative ways to maximise resources and foster multi-level collaboration- and both speakers had many lessons for others here.

As such, the Cities Northern Netherlands’ research explores possible and/or valuable programmes and funding opportunities for advancing gender mainstreaming agendas.

For example, the Multi-Annual Funding Framework for 2021-2027 is underway with 1.074 trillion EUR funding, which promises a tangible impact on equality if gender mainstreaming tools are well integrated.

Umea too- as lead partner in the Gendered Landscape network organised by URBACT, an EU-funded program- drew on international support. URBACT has built on the 2019 Gender Equal Cities initiative by partnering with institutions such as the Committee of The Regions and the Joint Research Council to promote ideas and encourage debate.

Start bottom-up… to avoid going tits-up!

While support from above has been instrumental in Umea and Northern Netherlands’ successes, their collaboration with local grassroots organisations has secured the targeted action required for understanding the intersectional needs of their inhabitants.

“Asking questions is about 80% of my workday!” said Gustafsson. “We need to really understand whom we are planning for.”

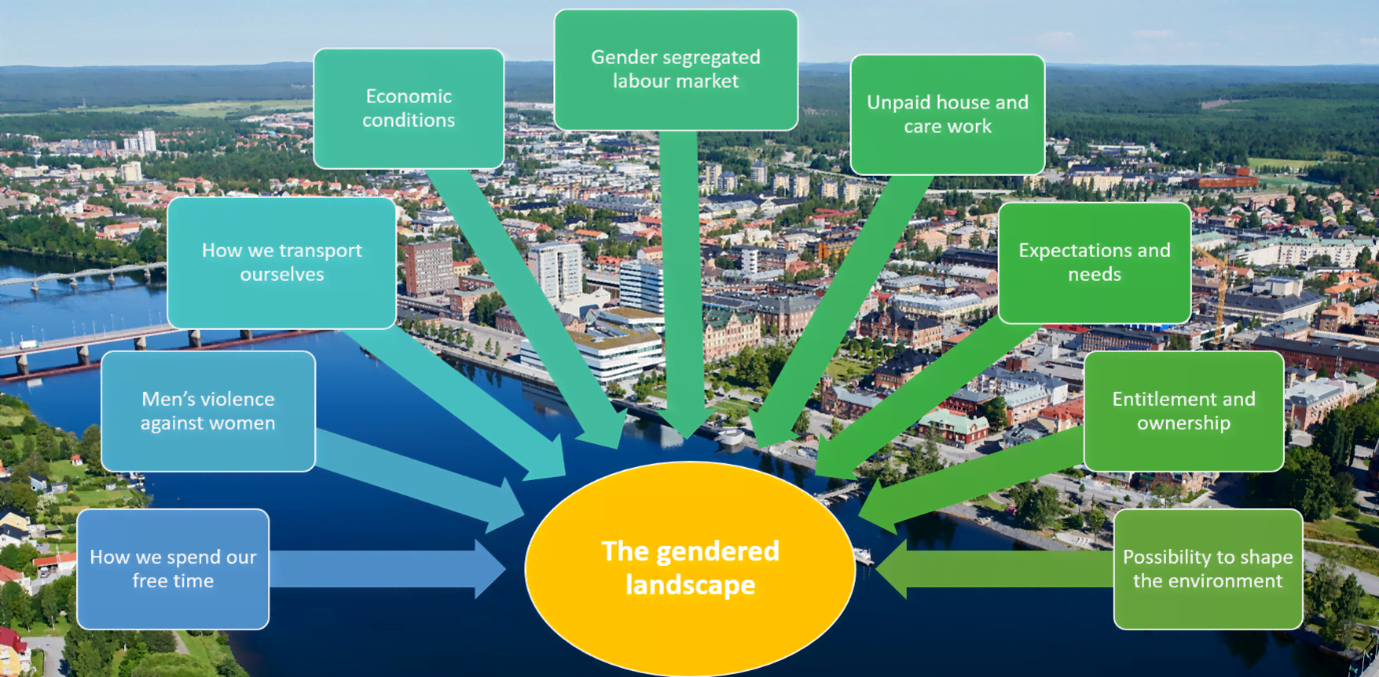

Image: some of the key factors shaping gender equity in cities. Source: Slide from Linda Gustafsson’s presentation

What is intersectionality, and why is it important for mobility? A quick recap

To take an intersectional approach to gender mainstreaming denotes the comprehension of a multiplicity of nuanced experiences and power relationships beyond an essentialist man-woman binary. Gendered experiences are shaped by a range of other factors including sexuality, (dis)ability, race, age, socio-economic status and more.

Thinking intersectionally about urban mobility means avoiding treating “women” as a uniform or singular “vulnerable user group”. It means acknowledging that women are impacted by transport infrastructure and services in varying ways, with marginalisation felt in different ways in different circumstances- often at different points across an individual’s life.

This is not necessarily a “layering” of oppression, but rather the ways multiple axes of identity unite to forge an individual lived experience- in this case of urban space and mobility.

For example, POLIS member, Sustrans’ work with Muslim women in the UK, their focus on age-related mobility patterns and research on mental health and active travel, has helped reveal and tackle the complex issues at play behind mobility choices and avenues for encouraging and supporting more sustainable and healthy choices for women from a range of backgrounds.

You can learn more about this HERE.

Not everything will be a success- but it is all a learning curve!

As most (if not all) those working in urban design and planning knowledge, behind every successful project or initiative are several dead ends, tactical changes, methodological adaptations, and even full-on U-turns. Now, nobody likes talking about their ‘failures’, but recognising and sharing missteps and hiccups are critical to the open and honest dialogue needed for successfully advancing gender mainstreaming.

The webinar was a chance to hear where these cities had perhaps gone wrong, and what this had taught them about how to integrate gender perspectives more effectively.

“In my opinion, our key mistakes are we need to talk to those who use the urban space more, understand gender perceptions,” said Palsma.

Interestingly, Umea’s guided bus tours around the city show successful changes in the city, yet also highlight enduring gender inequalities

There is always space at the party: The role of city-to-city cooperation

For both Palsma and Gustafsson, cooperation between cities has been indispensable in integrating and enhancing gender mainstreaming.

Establishing a clear pathway for such collaboration was at the heart of the research presented by Palsma. Northern Netherlands and the Groene Metropoolregio Arnhem Nijmegen already boast a strong partnership, particularly for mobility planning; and the research identified capacity for further collaborative working on gender equity. Indeed, as chair of the POLIS SMC Platform, the Northern Netherlands invests heavily in cooperation forums and mechanisms.

A feminist future for mobility

As this webinar revealed, gender mainstreaming mobility demands new ways of approaching urban planning which bends, stretches and even transfigures conventional practices. New ways of thinking, organising and collaborating.

Yet, as cities limber up to tackle a looming climate crisis, it is not just achieving gender equality which necessitates such transformative change; access regulations, alternative fuel infrastructure, public transport services, freight- the list goes on- will need to be part of the systematic change required to sustainable and accessibility mobility.

Movements towards making our cities more gender-friendly will simultaneously offer a new lens and framework for practitioners and decision-makers across the transport sector. Feminism is for everyone!

You can read the full version of the report HERE.