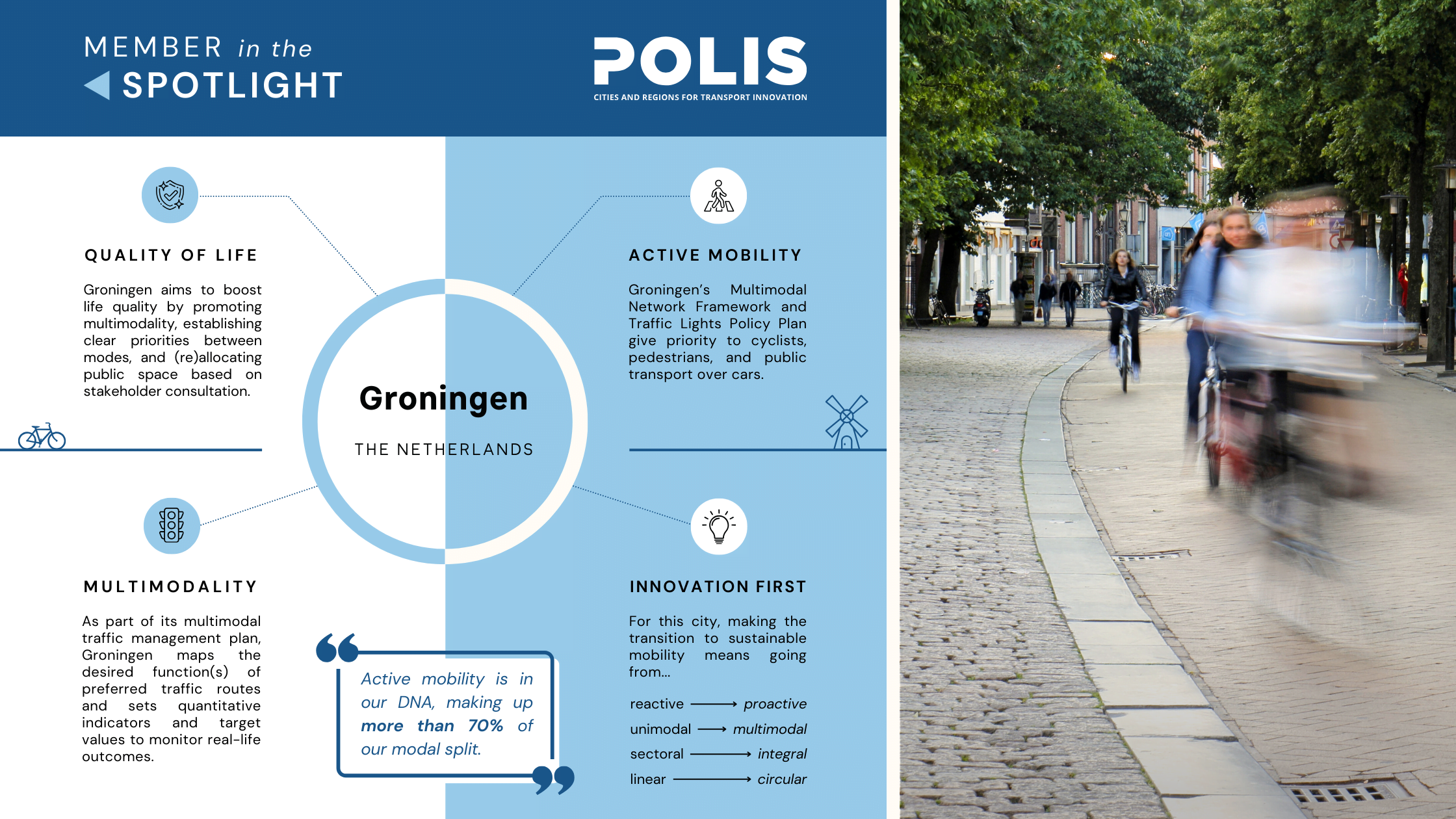

Member in the Spotlight: Groningen

'Member in the Spotlight' is back! To start the year off, we spoke to Groningen, winner of the 2023 Annual POLIS Award. From its support for active mobility to its engagement of stakeholders in urban planning, this city is well on its way to achieving a just and sustainable mobility transition. Read the full interview below!

Interview with Terry Albronda, Policy Advisor on Smart Mobility, City of Groningen, elaborated by Quaid Cey.

A thriving multimodal transport network, bike-friendly streets, zero-emission logistics… Groningen’s list of sustainable mobility goals could go on. But for this Dutch city, sustainable mobility is more than just a goal: is it a reality in the making, fostered through forward-thinking policies, support for innovation, and years of peer-to-peer cooperation with regional partners.

As the largest municipality in the Northern Netherlands and home to a top-ranking international university, Groningen has experienced massive growth in a short period of time, requiring the city to anticipate the mobility needs of tomorrow. In 2021, the city published its Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP), aptly titled “Groningen Well on the Way.” Alongside its 2023 Multimodal Network Framework and Traffic Lights Policy Plan, Groningen’s SUMP has helped to set clear priorities for future development, with better life quality ranking first across the board.

While two-thirds of city travel is already conducted by bike, Groningen has made it clear that more is needed: more infrastructure for cyclists, more protection for pedestrians, more public transport users, more publicly available EV charging, and more zero-emission trips. All are fitting goals for a participant in the EU’s Climate Neutral Cities Mission and the winner of the 2023 POLIS Award.

To get the full scoop on Groningen's sustainable mobility plans, POLIS spoke to Terry Albronda, the city administration's Policy Advisor on Smart Mobility. He told us more about the city’s ambitious traffic management policies, its effort to support active travel, and its aspirations for a carbon-free future.

POLIS: What does ‘sustainable mobility’ mean to the city of Groningen?

Terry Albronda: Groningen is known as a municipality that dares to implement a progressive traffic policy. Active mobility is in our DNA, making up more than 70% of our modal split. For us, achieving sustainable mobility means becoming an easily accessible municipality where pedestrians and cyclists are provided as much space as possible, with a future-proof public transport system in place and a robust car network that is designed for lower speeds. Ours is a municipality where smart mobility solutions such as shared mobility are commonplace and where experiments and innovation are warmly welcomed. We explicitly opt for mobility that takes up little space and is clean and healthy.

POLIS: How has Groningen effectively balanced its sustainable mobility goals with the needs of an ever-growing population?

Terry Albronda: 20,000 new homes and 15,000 jobs will be added in Groningen between now and 2035. This means that more residents (and visitors) will want to use our public space. As the city densifies, the pressure on public space will increase. The crucial question, then, is how we can keep Groningen accessible, liveable, and attractive, which forces us to make new choices.

Groningen city center. Credit: Alexander Bagno, Unsplash

'Quality of life' leads the way in everything we do, and it must be the reference for all of our design plans. By ensuring that our public space is safe, accessible, and suitable for gathering, exercising, and playing, we can make public space a force for social cohesion and better quality of life. At the same time, we can contribute to climate adaptation. With these goals, we are aligned with what many residents of Groningen consider important.

Our progressive traffic policy has already brought us a lot. We are now adding another logical step: giving priority to public space over traffic space by creating liveable, attractive streets and changing travel behaviour in favour of spatially efficient, clean, and healthy transport. Examples of such measures include cuts in car infrastructure. We consciously choose for active mobility and not for the shortest route by car.

POLIS: How has peer-to-peer collaboration with other cities, both within the Northern Netherlands group and through European projects, contributed to Groningen’s sustainable mobility efforts?

Terry Albronda: We increasingly see that the mobility challenges we face are more or less the same for everyone. Working together has added value: by working with partners at home and abroad, we gain new knowledge and experience, and new ideas are often born. With some funding, we can realise ambitious projects and accelerate transport innovation.

POLIS: In 2023, Groningen launched its Multimodal Network Framework to map out preferred traffic routes across the city. An important component of this policy was the creation of ‘function profiles.’ For those unfamiliar with the concept, can you explain how a function profile works?

Terry Albronda: Sustainable regional and urban mobility requires a broadly supported, multimodal vision regarding the desired use of transport networks. A multimodal network framework (MNF) offers that vision. In fact, it is the translation of mobility policy into an unambiguous description of the 'desired situation' for (multimodal) transport networks.

In an MNF, you can roughly distinguish between four building blocks:

- the preferred routes to the most important destinations in a city or region;

- function profiles and their associated functional map;

- multimodal priorities;

- and the reference framework.

While function profiles provide a qualitative description of the desired functioning of networks, the reference framework makes this measurable in terms of indicators and target values.

To test whether transport networks will be used correctly, it is important to determine the desired functioning of cars, public transport, and bicycle lanes for each road type. Therefore, a function profile is drawn up for every type of road in the MNF. The following elements appear in such a profile:

- Function: To determine the function of a road in the network, we ask questions like “What type of relationship (internal, ongoing, external) is facilitated?”, “Is this a short- or long-distance relationship?”, “Which type of user is prioritised?”, and so on.

- Traffic characteristics: When it comes to traffic characteristics, we look at things like the bundling of traffic flows and the safety, reliability, and comfort of connections.

- Testing: Here, our goal is to determine how traffic characteristics can be measured and tested. This is the prelude to the drafting of a frame of reference.

- Basic principles of design and equipment: The recognisability of a given function is essential for road safety and quality of life. Therefore, we also include principles for the design of the road profile and the equipment that is part of a given part of the network.

The result is a set of function profiles that describe the different types of roads in an urban transport network. By projecting the function profiles onto a map of that network, we get what we call a “multimodal function map.”

Here are some examples of function profiles:

- Bicycle highways: As important regional connections between residential and working areas, bicycle highways cater to the fast and continuous cyclist. Few or no traffic lights are in place, and wherever possible, cyclists are granted priority at intersections. Trails are wide, comfortable, and well-maintained.

- Connecting cycle path: The urban equivalent of bicycle highways, these paths connect residential and working areas within Here too, comfort and speed are important, but because of the urban setting, there are more intersections and crossings. On these routes, bicycles are preferably separated from other traffic flows.

- Urban distribution road: The main purpose of an urban distribution road is to evenly distribute traffic towards important economic centres and prevent regional congestion.

- Urban access road: The urban access road ensures reliable access to core areas and distributes traffic across the core area of a city. These roads connect higher-order roads (such as urban axes, which link urban distribution roads to the inner city) with shopping, parking, and residential areas. Depending on the road’s location, cars may not be a priority, and extra attention may be paid to public transport and “slow traffic.”

Let me illustrate the concept with an example: We can use the MNF to see which functions come together at an intersection with traffic flow problems (building block 2). Available data can then be used to visualise the quality of each function (building block 4). The priority order (building block 3) can then be used to identify solutions in line with traffic policy.

POLIS: Groningen has identified accessibility, quality of life, and road safety as essential criteria to consider when planning traffic management measures for preferred routes. Concretely, how is data collected for each of these indicators?

Terry Albronda: In the reference framework, we make clear how the quality of the network can be measured with indicators and target values. As in many cities and regions, data availability and quality are not always the same for the different modalities. In Groningen, for example, we have high-quality data for car traffic, which has allowed us to assess the state of our car network for several years. Currently, we use floating car data from our national access point to visualise the flow and reliability of the city’s car network.

A cyclist in Groningen. Credit: nataliajakubcova, Shutterstock

Indicators for public transport and cycling are still in development. When it comes to public transport, we use historical data from the national open database, which mostly consists of the location messages of all buses, trams, metro, and trains. As for bicycle traffic, we rely on the results of loop detectors and information from intelligent traffic lights. We are still investigating which (new) data sources will be needed to elevate public transport and cycling data to the same level as the data we have on cars.

POLIS: The city has done much to improve the allocation and management of its urban space, with tangible benefits in the area of mobility. Some would say Groningen has successfully implemented the ‘15-minute city’ concept. For other cities looking to achieve similar results, where would you recommend to start?

Terry Albronda: Our advice is to put people first. That means prioritising pedestrians, then cyclists, followed by public transport, delivery vehicles, and finally, cars. Emergency services clearly have an exceptional position in this ranking. By focusing on the everyday experience of city residents, it becomes clear that the quality of the living environment is of the utmost importance, and that mobility is an important part of this living environment. Therefore, it is crucial to include broader welfare objectives in integrated traffic management plans. A better living environment can be achieved by distributing mobility more evenly between various modes, setting clear priorities, and designing accordingly.

POLIS: How does Groningen involve the local community in the decision-making process regarding street space reallocation and the city’s multimodal network?

Terry Albronda: We create Groningen together. By allowing stakeholders to influence developments in the city, we ensure that Groningen belongs to everyone.

Ultimately, we want to break through the government’s traditional sectoral approach. For this, the scale of neighbourhoods and villages is ideal. We experiment with far-reaching direction and monitoring by local communities. Our objective is to achieve sustainable democratic renewal and an integrated, place-based way of re-working the city.

Not only is it our ambition to involve the people of Groningen in our work – participation is also a legal obligation, which applies to every project or policy assignment uniquely. To work in a structured manner, we have developed a participation manual, which explains how to create, implement, and evaluate a participation plan for any project.

POLIS: Another example of Groningen’s innovative approach to traffic management was the 2023 Traffic Lights Policy Plan, which helped give priority to pedestrians, cyclists, and public transport over cars. Shorter waiting times at traffic lights have been one of the main benefits of this plan. Can you expand on this?

Terry Albronda: Intersections form important links in the mobility network. The quality of Groningen’s traffic network, as described in the MNF, is partly determined by the quality of our intersections. Therefore, we have made traffic lights an important part of our approach through the Traffic Lights Policy Plan.

Cyclists in Groningen. Credit: Denise Jans, Unsplash

In the near future, we want to make cycling and walking the easiest and fastest ways to get around Groningen. Because the Sustainable Mobility Plan already succeeded in giving priority to walking, cycling, and public transport, translating this into short waiting times at traffic lights was a logical next step. By first experimenting with traffic light measures at a select number of intersection locations, we will be able to decide whether our ambitions are feasible in practice. Then a rollout to the other locations with traffic lights can be planned.

POLIS: How does Groningen plan to make its multimodal transport network even more sustainable in the years to come?

Terry Albronda: After adopting our Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP), we are fully engaged in the implementation of many new mobility projects. Currently, we are working on the creation of a zero-emission zone in the city centre, while at the same time trying to introduce more public EV charging infrastructure, develop better parking facilities for bicycles, and roll out district and neighbourhood mobility hubs with facilities for shared mobility.

In the coming years, we will continue to reclaim public space in developed areas. In new development areas, we can deal with mobility differently, focusing on quality of life from the outset. We will also embrace the possibilities that new, intelligent traffic lights offer and look further into the future with our new vision on traffic management. Some of the key concepts that currently guide our plans are ‘from reactive to proactive,’ ‘from unimodal to multimodal,’ ‘from sectoral to integral,’ and ‘from linear to circular’ – in short, enough initiatives to make the city more sustainable, day by day.

An overview of Groningen's current measures in the area of innovative and sustainable mobility. Design by Quaid Cey.