The liveable train station

The future of mobility as we know it is depicted with undeveloped flying objects and autonomous machines carrying suited people in a highly effective manner. We have got used to talking about the future of mobility in this way and keep talking about how smart our cities will be, without actually discussing how we would like our cities to be in the future. Simon Wind and Gustav Friis look to get the discussion going…

In late September 2019, the mobility department at the City of Aarhus travelled to the Dutch cities of Amsterdam, Utrecht and Arnhem to have a direct look into the future. All these cities have made impressive transformations of their main train station areas and we wanted to have a closer look at what had been achieved. Over three intensive days, the delegation of 20 mobility planners were guided through the three station areas by representatives from Benthem Crouwel Architects and the city administrations of Utrecht and Arnhem.

Being in the very initial phase of a re-designing process for the main train station area in Aarhus, this study tour not only gave good advice, inspiration but also raised questions on how a long-lasting process of redevelopment can be shaped. We are planning for an efficient future mobility system, but we are also planning the future city.

This article reflects the authors’ views and learnings and what we intend to bring with us back to Aarhus and the planning process for the redevelopment of the main station area.

DESIGNING FOR FLOW

When visiting the main train station areas in Amsterdam, Utrecht and Arnhem the first aspect that struck us was not only the scale and careful interweaving of transport modes, but also the sheer efficiency. Behind the station design, we learned, lies a clear strategy of managing large quantities of travellers that move through the urban centres every day. This is very evident in Amsterdam and Utrecht where the station areas are by the use of architecture, materials, lighting, wayfinding, nudging and crowd management designed as traffic machines par excellence.

To understand this, one must see the central role that the main station areas play in transitioning the major Dutch urban regions from being primarily car-based towards multi-modality. As one representative from the City of Utrecht stated, from the middle of the last century the focus was to facilitate the car – cities were planned and built around car infrastructure which only led to more car traffic and more infrastructure and less attractive cities. In the late 1980s this focus shifted towards public transport and, in the Netherlands, to biking, in order to create calmer and liveable cities.

From the middle of the last century the focus was to facilitate the car - cities were planned and built around car infrastructure which only led to more car traffic and more infrastructure and less attractive cities

The four major cities in the Randstad area in the Netherlands, the pan-urban region encompassing Amsterdam, Utrecht, The Hague and Rotterdam, have taken a stand towards the car and urban sprawl in a radical manner. In this vision, liveable and attractive urban regions should not be dominated by car traffic and public transport: biking and walking together with transit-oriented development and densification should be (and indeed are) prioritised.

At Amsterdam Centraal, the metros, buses, trains, trams, pedestrians and bikes are stacked in layers. At Utrecht Centraal, traffic functions are neatly juxtaposed next to each other. In Arnhem, the traffic function area is clustered around a snail shell shaped terminal. The individual traffic functions are knitted together with strategically placed pedestrian and bike routes, hallways and corridors that also interweave the station areas together with the surrounding urban fabric.

Knowing the limitations and challenges in Aarhus, what we found particularly impressive was how it has been possible to re-organise and gather existing traffic function, as well as introducing new ones (i.e. light rail) in more logical and efficient setups at this scale and in the existing urban centres, which have a notorious lack of space. These steps require not only economic muscle but also political will and foresight. In Amsterdam it has taken 20 years to come to this point and the station area is still under development. It is the same picture in Utrecht and Arnhem. These large-scale projects are best understood as new urban districts that are not developed overnight but over decades.

Importantly, we learned that the development of all the major station areas is handled in consortiums of key stakeholders. In the case of Arnhem, the consortium consists of the city of Arnhem, Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen, NS, ProRail, and several private landowners and investors. Although such consortium constructions with varying individual and often conflicting interests are a challenge to manage in themselves, they are a necessity in successfully negotiating, creating support and accomplishing complex large-scale projects as we have seen.

Importantly, we learned that the development of all the major station areas is handled in consortiums of key stakeholders. In the case of Arnhem, the consortium consists of the city of Arnhem, Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen, NS, ProRail, and several private landowners and investors. Although such consortium constructions with varying individual and often conflicting interests are a challenge to manage in themselves, they are a necessity in successfully negotiating, creating support and accomplishing complex large-scale projects as we have seen.

DESIGNING FOR LIVABILITY?

The main station areas in Amsterdam, Utrecht and Arnhem are best comparable with airport terminals. They deal in capacity, reliability and safety first and foremost. Instrumental flow space is not particular pleasant to travel through or linger in, therefore in the design of the stations there is also a strong focus on endowing transit space with liveability and public space qualities.

What we learned was that in the design of all three station areas there are ambitions to be more than just generic traffic machines: Amsterdam, Utrecht and Arnhem’s stations wish to become places that give something back to their respective cities, and in themselves are attractions with urban qualities and attractiveness. As Benthem Crouwel Architects, who have designed a majority of all the main train stations in the largest cities in the Netherlands, told us, their approach to create successful mobility hubs is to marry transit design with urban design. “At the heart of this approach there is an acute passenger perspective”, we were further told by the architects.

Therefore, the stations we have visited are designed to be places of travel as well as places to meet, linger, eat, shop, hang out, interact and play.

A key component in this recipe is the seamless integration of commercial programs into the station areas. Not just as convenient kiosks and newsstands to cater busy travellers, but also grocery stores, chain stores, hotels, cinemas, food courts, restaurants and cafés. Just as most airport terminals, there is a strong commercial programming – almost a shopping mall. Although the commercial program clearly is at a lower hierarchical layer than the flow, crowd management and traffic programs, it can transform the main train station areas into something more than just ‘traffic machines’. It is not a public space as other places in the city, since it is clearly gated, semi-private and regulated, but it is a hybrid of urban, commercial and transit spaces.

Moreover, all the station areas encompass opportunities for mixed use urban development of offices, residential programming, public services and plazas. This transit-oriented development approach furthers the shift of the station areas from ‘traffic machine’ to urban district, however, still without abandoning the main purposes of transit and transfer.

A strong architectural motif at all three station areas is the gathering of all traffic functions, commercial programs and spaces under a single roof in one megastructure of many juxtaposed and stacked bodies. Besides the obvious comforts of being able to travel efficiently and sheltered from weather, it provides calmness, a sense of safety, order and coherence that makes the choice of public transport and green modes of mobility even more attractive.

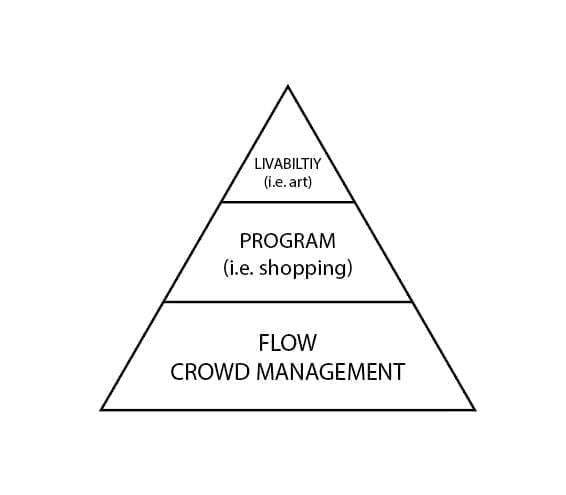

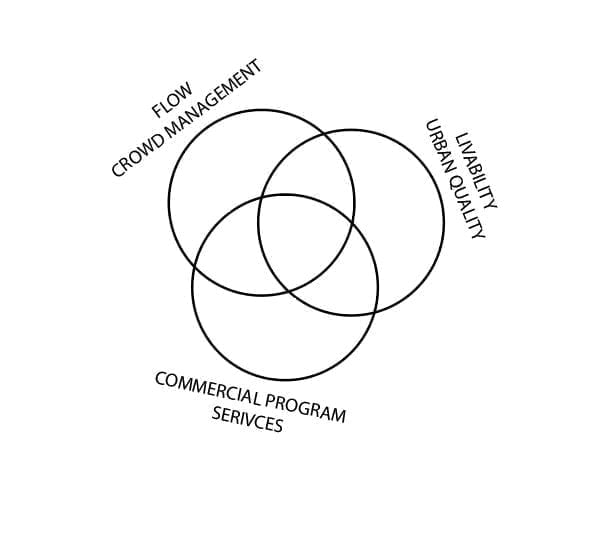

From a hierarchical perspective towards an integrated planning approach for future mobility hubs

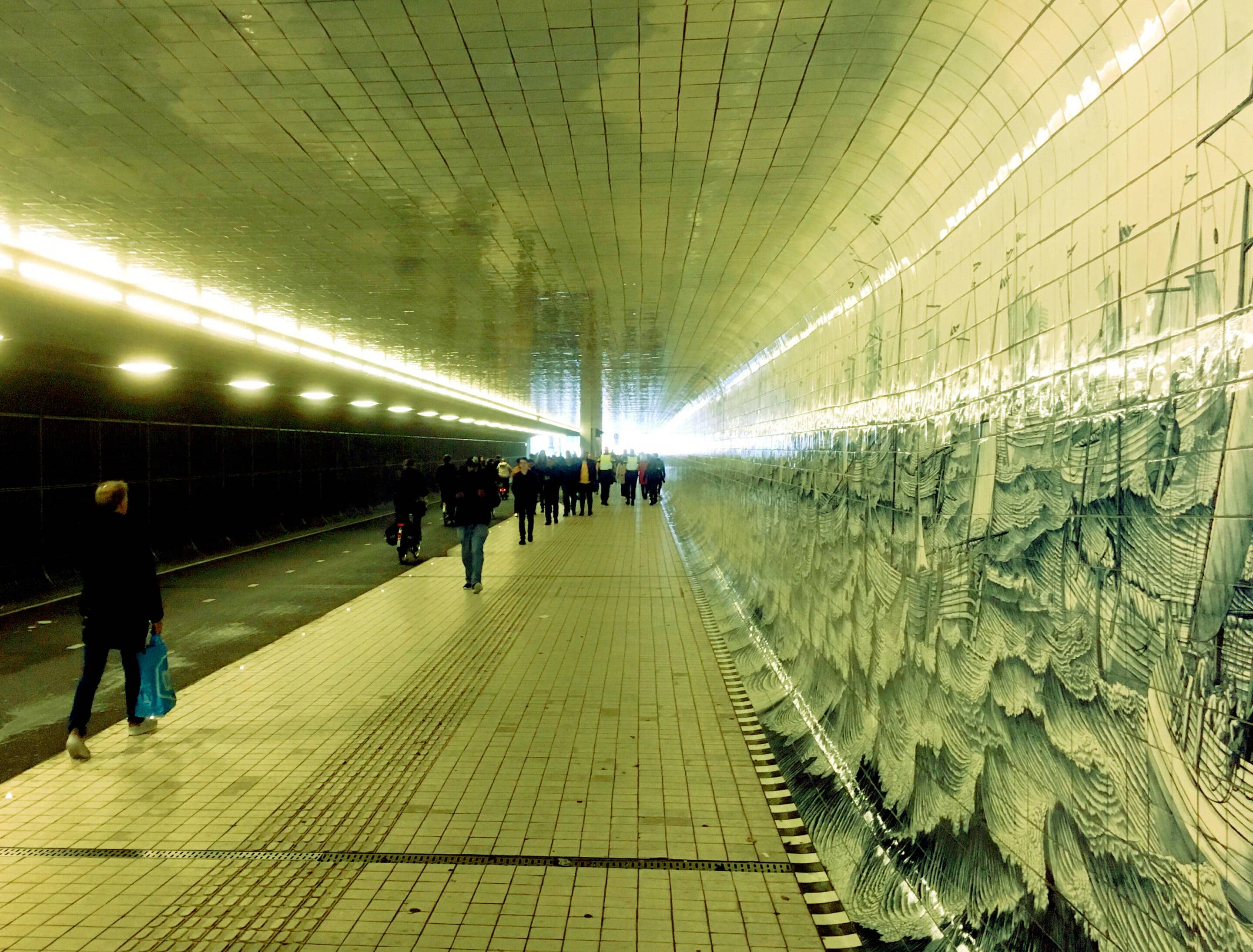

Finally, at strategic locations in station areas the use of decoration, art and media installations are used to further underpin the hybridity of the space. In the metro underneath Amsterdam Centraal, there is for example a large screen installation showing a new landscape every day while forecasting the weather. This is both distraction of the fact that we are travelling deep underneath ground, without fresh air and natural light, and it is a bit of green, although artificial, choice, that softens the hard surfaces within the environment of the metro.

The large-scale architecture in the station areas is by itself designed to be characterised by landmarks that can be seen from afar and act as lighthouses for wayfinding. But they also underpin the station areas as a distinct part of the urban fabric, thus bringing counteraction to the city’s other more historical landmarks. In Utrecht the main plaza next to the station complex is covered with a tall, white roofing on high pillars and with a bubble-like structure. In Arnhem, it is the station building itself that is the landmark with its curved and organic silver-clad shape.

The use of these small- and large-scale artistic installations and landmarks embedded in the stations areas contributes to the transformation of generic transit and commercial space into places with atmospheric character and spatial qualities. This overall brings the station areas we have visited in this study tour one step closer to moving beyond the traffic machine and to start flirting with the feel of liveable and vibrant urban and public spaces in the city.

Imagine a future train station as an extension of the inner medieval city centre, where wayfinding measures are lowering the pace of the travellers, where the shops are not fast food restaurants and where the experience of being on the go is like taking a stroll in the city

BRINGING IT ALL INTO THE FUTURE

The train station in Aarhus has approximately 30,000 transfers every day and is in that way mostly comparable with the one in Arnhem with its 38,000 transfers per day (although Arnhem city itself is only half the size of Aarhus).

Being a relatively small hub in a larger city should hopefully make it possible to break down the hierarchy explained in the pyramid figure, and start working in a more integrated way by combining crowd management with commercial programming and urban quality. With this mindset, the transition from the urban landscape to the traffic machine could potentially be postponed to the moment the passenger is about to board the train or even be eliminated.

Imagine a future train station as an extension of the inner medieval city centre, where wayfinding measures are lowering the pace of the travellers, where the shops are not fast food restaurants and ‘grab and go’ concepts, and where the experience of being on the go is like taking a stroll in the city. Could this be achieved while still maintaining efficiency and flow, however, at a slower pace? Could this be the train station of tomorrow?

Simon Wind and Gustav Friis are Mobility Planners at the City of Aarhus, Denmark

siwi@aarhus.dk

guf@aarhus.dk