Best foot forward

Walking and cycling can boost local economies and people’s well-being. Heather Allen and Elah Matt share examples of how promoting walking and active travel can benefit local businesses and inclusiveness

Many cities are prioritising walking and cycling in their centres, but others still hesitate to restrict car access to central shopping and business districts. This is partially due to resistance from local businesses, retailers and visitors. A key barrier is the perception that restricting car access will negatively impact the numbers of people visiting the area for shopping or leisure. However, research shows that pedestrians and cyclists spend as much or more time engaged in those activities than people who come by car. Typically, retailers also overestimate the importance of car access to their customers.

For several decades, city centre retail has been challenged by changing shopping patterns. Initially, the rise of car-dependent, out-of-town shopping malls posed competition to local businesses and more recently, the rise of internet shopping has changed the way we shop. Both ‘traditional’, on-street retailers and shopping malls now find themselves in a highly competitive market that increasingly relies on providing a unique ‘shopping experience’, rather than only on price. The need to provide attractive urban shopping environments is thus increasingly important. This article presents several successful examples that can be used by city authorities to address concerns raised by the public and local businesses and outlines how pedestrianising shopping areas can help retain their dynamism and attractiveness.

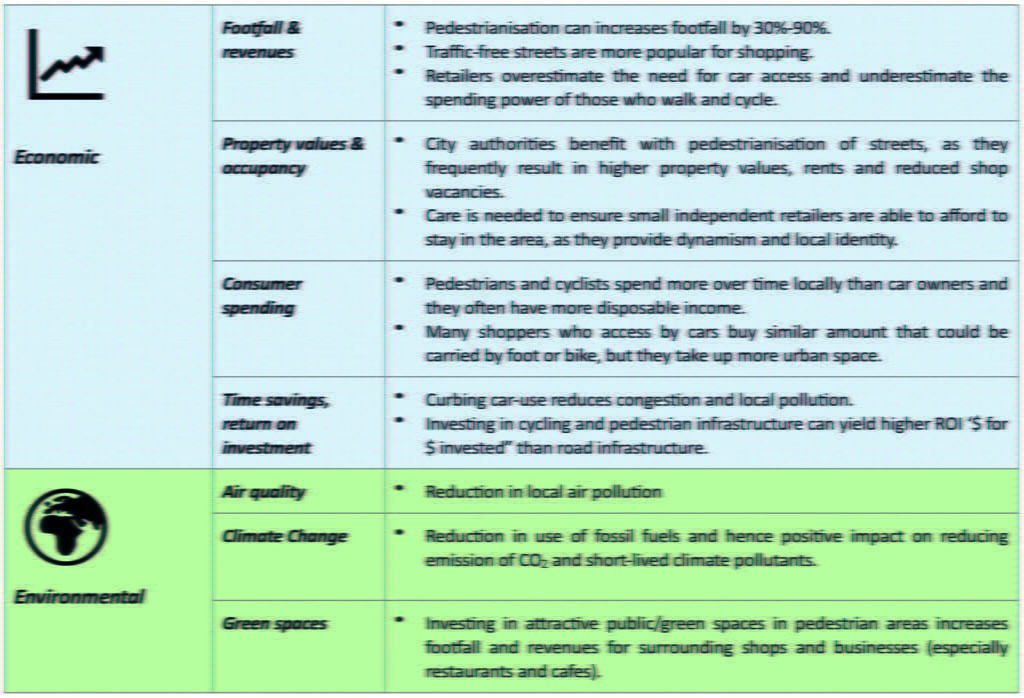

Table 1: Key benefits of investment in walking and cycling zones. Source: Table based on several sources and developed by the authors

THE BENEFITS OF PROMOTING WALKING AND CYCLING

Mounting evidence shows that when public spaces are made attractive to ‘slow modes’ of travel, allowing people to walk and cycle safely, people spend more time and money locally. The European Cyclists Federation found that doubling the modal share of cycling in the EU (from 2015 levels) would generate an increase in retail turnover for local retailers of over €27 billion1 .

Amongst other benefits, numerous studies show an increase of 10-40% in revenues following pedestrianisation2 . Property and rental values often increase, ranging from 7.5% in a recent London study to 300% in Canada3 . Pedestrianisation and urban regeneration can also increase the number of local businesses and jobs, as seen in Dublin’s Temple Bar District, which experienced a 300% increase in employment and a rise in number of local businesses from 60 to 450 within a decade4 .

Overall, there are numerous economic, environmental and societal benefits to promoting walking and cycling and restricting vehicle access to specific areas, as summarised in the table above.

SHOWING THE WAY

There are a wide range of ways to keep town and city centres attractive and dynamic. Some cities, such as Oslo, are looking to ban all cars, while others, such as London and Madrid, are restricting access to more polluting vehicles. Copenhagen led the way by pedestrianising the 3.2km long “Strøget” central shopping street in the historic centre in 1962, mainly for traffic-safety reasons. The following cities have successfully pedestrianised central shopping areas.

Vienna

Vienna began to pedestrianise its centre in 2011. The central shopping street, Mariahilfer Straße, is the most important shopping area in the city, representing 10% of retail sales volume, so making changes had to be carefully managed. The city invested in extensive public engagement, presenting plans and models to help visualise the redesign ahead of pedestrianisation. A yearlong trial ensued and was evaluated with roundtables and surveys. This approach allowed people to voice their opinions and make informed decisions about the scheme. A referendum was then held, resulting in just over 50% of people favouring pedestrianisation.

The narrow majority included strong resistance from some business groups, media and political parties, combined with opposition from some residents to change. The results showed the importance of the extensive public-engagement strategy in gaining support and ensuring the acceptability of the scheme. Now visitors, residents and shopkeepers are very positive about the transformation. In an ex-post evaluation, 71% of respondents said they would vote in favour of the scheme and 55% stated that travel modes interact well with each other. Some 38% of shopkeepers stated they experienced a rise in sales while 46% stated that business was unchanged. The street transformation increased social interactions and decreased air pollution from vehicles, enhancing public health. The overall cost of €23.3 million can be contrasted with the renovation of a mall outside of Vienna, costing €150 million5 .

Munich

Munich established its central pedestrian area in the early 1970s, as part of preparations for the 1972 Olympics. Improved public transport would get people to the car-free main square, Marienplatz, and the city hall. Retail turnover and footfall increased significantly following pedestrianisation6 . Kaufingerstrasse, the main shopping street, is today the second most popular in Europe, with an hourly footfall of over 12,800 people7 . In 2016, Sendlinger Strasse8 , another popular shopping street, was pedestrianised for a 1-year trial, as local retailers were sceptical about pedestrianisation and particularly concerned about how delivery times would work9 . Based on its popularity, it was made permanent in 2018. Upgrading the pavements and street furniture will cost €3.5 million (expected to be completed in 2020)10.

"Over 250 streets in Istanbul are pedestrianised, with roughly 2.5 million visitors daily. Traffic fatalities are down by an estimated 60%"

Istanbul

Istanbul’s historic peninsula provides an iconic example of successful pedestrianisation. The UNESCO World Heritage site was severely challenged by traffic congestion, air pollution and road safety issues11. An initial study examined possible impacts on the environment, traffic, trade and other issues. Pedestrianisation was then introduced gradually. Initially around the historical landmarks, then expanded slowly into the surrounding streets. A post-implementation survey was conducted among local workers and visitors:

Some 80% answered positively about the impact on the physical environment; 89% of visitors agreed that travel and shopping were more comfortable and 82% felt safer; 82% of the tradesmen said they had benefited from pedestrianisation, with a 76% increase in visitor numbers. A 44% increase in bicycle use was also observed. Significant improvements in air quality and noise levels were reported. Those surveyed were generally happy with pedestrianisation and optimistic about the economic vitality of the area, with an overwhelming 83% saying they would support further pedestrianisation.

Today, over 250 streets in the Peninsula are pedestrianised, with roughly 2.5 million visitors daily. Traffic fatalities are down by an estimated 60% and 65% of employees and visitors use public transport.

New York

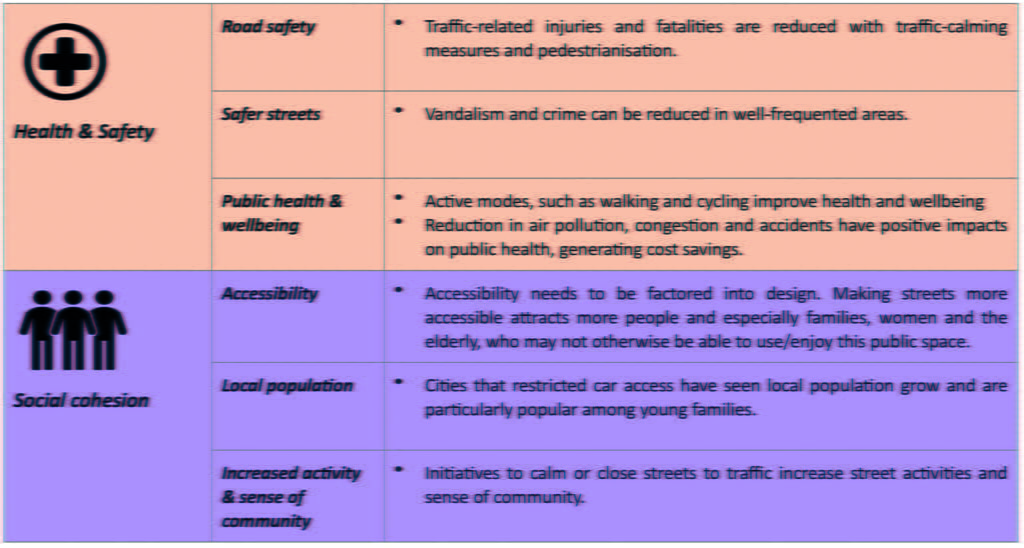

New York City has a large walking population and a growing cycling community12. Following an increase in the number of traffic accidents in the Times Square area, in 2009 the city’s Department of Transportation decided to close Broadway to vehicles and created a trial pedestrian-only zone. Five blocks stretching from Broadway through Times Square became an ad-hoc park with painted areas on street, deck chairs and tables. The project improved road safety, reduced travel times and increased business, so Mayor Bloomberg made the scheme permanent.

The use of temporary measures – paint, temporary street furniture, art installations and planters – allowed the city to test ideas and gain the support of the community quickly, rather than waiting for planning reviews or studies. This ‘ad-hoc’, or tactical urbanism, approach led to the creation of more than 60 pedestrian plazas across the city, converting more than 26 acres of car lanes to spaces for people. It has been replicated in cities across the world – from Boston to Los Angeles, San Francisco and Buenos Aires.

Times Square before and after tactical urbanism interventions

Source: New York City Department of Transportation

DRIVING CHANGE

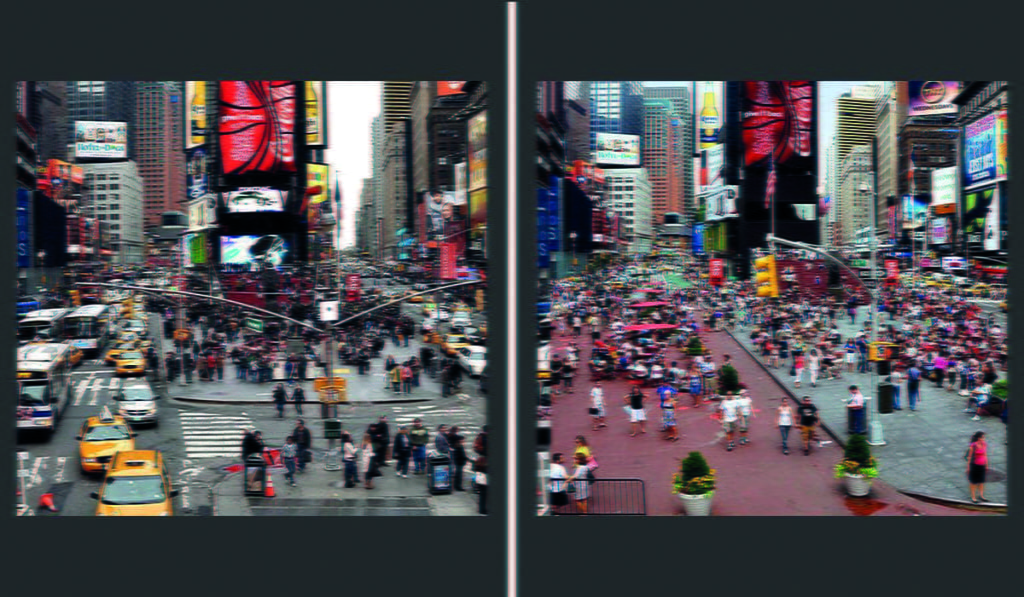

The successful examples given below have several common elements: they encouraged public engagement, created a common vision that was adaptively implemented to the local context, and evaluated impacts.

Engaging the public is vital for gaining support. Consultations, surveys and a referendum were carried out in Vienna, enlisting support from residents and retailers. In Istanbul, several studies and surveys were conducted by local NGOs to gauge people’s attitudes towards pedestrianisation and impacts on local mobility and retail.

Envisioning change and how pedestrianisation can be implemented helps to increase public acceptance. In Vienna, models of the pedestrian zone were shown to the public. A pilot scheme ensued, demonstrating how the scheme would work in practice. In New York, a more radical approach was adopted – showing people how pedestrianisation would look through ad-hoc street closure and other tactical urbanism measures.

Implementation needs to be adapted to the local context. In Istanbul, pedestrianisation of the historic peninsula was rolled out incrementally, but quickly, whereas in Vienna full implementation took longer (around three years). Gaining public support and creating a common vision are likely to influence how quickly pedestrianisation and other traffic-calming measures are rolled out.

Evaluation, both before and after implementation, is key to assessing public opinion and impacts on local businesses, street users and environmental conditions.

Figure 1: Framework for supporting uptake of pedestrianisation schemes

MOVING FORWARD

Urban retail centres need to remain attractive for people to visit them and spend money. When these centres suffer from traffic congestion and high levels of air pollution, people tend to avoid them. Investing in pedestrian and active-travel infrastructure has proven to be economically beneficial, with cyclists and pedestrians often spending more than drivers over time13. A range of other economic, social and environmental benefits are also commonly observed, as outlined above.

Strong political support and enabling policies are key. Crucially, it is important to build consensus and work with consumers, retailers and political decision-makers (who are also voters). Individual perceptions and mindsets play a vital role in framing people’s opinions. Carrying out before and after evaluations helps to show that when measures are successful people do shift their initial positions and mindsets.

Reducing access to private cars in urban areas is a delicate and often contested issue, but one that needs to be addressed for economic, social and environmental reasons.

FYI

NOTES

[1] European Cycling Federation, 2015, Shopping by bike: best friend of your city centre, https://ecf.com/sites/ecf.com/files/CYCLE%20N%20LOCAL%20ECONOMIES_internet.pdf

[2] Arup, 2016, Cities Alive: towards a walking world, Arup, London; Burden, D., Litman,T., 2011. “America Needs Complete Streets.” ITE Journal 81 (4): 36–43; Carmona, M et al., 2017, Street Appeal: the value of street improvements summary report, University College London, Transport for London; Hass-Klau, C. 1993, Impact of pedestrianization and traffic calming on retailing: A review of he evidence from Germany and the UK, Transport Policy 1 (1) 21-31; Hass-Klau, C. 2015, The pedestrian and the city, Routledge, Abingdon; Lawlor, E. 2014, The pedestrian pound: the business case for better streets and places, Living Streets, London; New York City Department of Transportation (2013) The economic benefits of sustainable streets, New York; Tasker, M. 2018, The pedestrian pound: the business case for better streets and places, Living Streets, London.

[3] Burden and Litman, 2011; Carmona et al., 2017.

[4] Lawlor, 2014

[5] Telepak, G. 2016, Transformation of the “Mariahilfer Straße” traffic reorganization to provide new pedestrian zones and shared space, http://www.eltis. org/sites/default/files/a2_telepak_mariahilferstrasse_vienna.pdf

[6] Hass Klau, 1993; 2015

[7] BNP Paribas, 2017, Pan-European Footfall 2017/2018, https://issuu.com/ newsecegeskovlindquist/docs/pan-european_footfall_2017_-_2018

[8] Part had been previously pedestrianised

[9] City of Munich, Department of Urban Planning, 2017, Work Report 2017/2018,

[10] Muenchen.de, 2018, https://www.muenchen.de/aktuell/2018-11/ sendlinger-strasse-wird-dauerhaft-zur-fussgaengerzone.html

[11] Evaluation Environmental and Social Impacts of Pedestrianization in Urban Historical Areas: Istanbul Historical Peninsula Case Study Demir H. et al, Journal of Traffic and Logistics Engineering Vol. 4, No. 1, June 2016.

[12] New York’s transportation Master Plan 2030 https://www.dot.ny.gov/portal/page/portal/main/transportation-plan/repository/masterplan-111406.pdf

[13] Carmona et al., 2017