Gender equal mobility: beyond the ‘vulnerable user’ paradigm

Challenging the ways we discuss gender-equal mobility is key to driving further change; this starts with interrogating the language of 'vulnerability'.

That our urban mobility systems fail women is no secret; however, an enduring perception of women as ‘vulnerable users’ is obstructing the comprehensive change demanded. We urgently need to view women as not just primary transport users, but also decision-makers; this means understanding how gender really operates.

From Vienna and Umea’s redesign of public space to Transport for London’s ‘Report it to stop it’, Safe.Brussels’ ‘Join the Fam’, and Manchester’s “Is this Okay” campaigns, there has been a range of initiatives to identify and challenge the ways mobility ignores- and indeed further marginalises- women.

However, building on this action requires a revisioning of ‘gendered’ mobility and the language we use to consider women and transport users- and decision-makers.

At present, we sling women in a ‘vulnerable user’ category when discussing gender issues surrounding transport. Undoubtedly, a continuum of violence against women, renders them more vulnerable than their male counterparts when navigating the city, YouGov research revealed that over a third (39%) of women in London have been subject to unwanted sexual behaviour while travelling on public transport, while a 2020 study in Catalonia put the figure nearer 65%.

Meanwhile, women’s outsized contribution to domestic labour and caregiving (they are responsible for 75% of global unpaid care work), is shamefully underserved by urban transport systems which ignore their resulting travel patterns.

While this language has - and continues to - successfully mobilise the attention and action urgently needed, we risk inhibiting truly ‘mainstreaming’ gender by unquestioningly clinging to this discourse of 'vulnerability' and the function gender plays here.

Women make up half of the population, and over 50% of public transport users in many cases; yet, with women as ‘vulnerable users’, the male transport user remains the norm and women as fringe travellers, maintaining the androcentrism which dominates transport planning.

This sweeping language of vulnerability also serves to obscure the ways race, sexuality, age, ability and socio-economic background shape gendered mobility experiences.

Not all women experience transport systems in the same way, and failure to scrutinise this, and bring a spectrum of women's voices to the fore, prevents a full understanding of how gender operates within multiple axes of vulnerability.

Moving forward? The panel discusses

Interrogating this was the approach at a recent panel at the Annual POLIS Conference in Brussels this year, which brought together cities, shared mobility operators and international gender experts for a workshop on the way forward.

The panel, from Left to right, Isobel Duxfield, Lucia Schlemmer, Grace Packard, Kate Barnes, Francois Hoehlinger and Heather Allen

'We can't change mobility for good, without addressing the gender imbalance in urban mobility,” stated Kate Barnes from Tier, who joined Grace Packard from Voi, Francois Hoehlinger from Troopy and independent consultant and gender expert Heather Allen- currently working on a study into women’s employment in the transport sector.

A caveat here: shared and micromobility is of course not the only players in ensuring gender-equal transit, nor even the most important; public transport operators, local authorities and law enforcement must be in the metaphorical (and perhaps physical) ‘driving seat’, nonetheless, the research and initiatives being undertaken by operators like those on this panel hold lessons for others looking to mainstream gendered transit needs and demands.

After all, supporting women’s usage is not just an issue of human rights- it is a sound business decision; for micromobility, as they seek to navigate a rapidly changing urban mobility landscape, understanding and catering to a range of demands are critical.

Women currently make up only 25 per cent of micromobility users, therefore reducing barriers to usage- treating women as core, not just fringe customers- is critical for sectoral growth.

The same is true for public transport; research in the UK forecasts the number of public transport users would increase by 10 per cent if passengers, especially women, felt safer. As the sector battles to recover pre-pandemic ridership, it cannot afford to overlook women.

Voi and Tier’s research into the factors shaping women’s ridership, exploring the location of services, accessibility of parking, safety and security indicate the plethora of ways gender affects travel experiences and choices- and (unfortunately) how much more work is required.

Tier’s study exposed the degree to which safety and security shape women’s mobility patterns. 31 per cent of women are concerned by a lack of lighting in parking areas and ¼ of women fear being stalked or followed. This plays out in the way they use services. Tier revealed that in the UK, 73 per cent of women would feel safe riding during the day, while a mere 3 per cent would feel the same at night.

Voi’s study echoes these findings. Their investigation into women’s perceptions of shared e-scooters, found services need to be better designed for women’s feeling of (lack of) safety and the wider ‘masculine’ ways micromobility is marketed.

It is important that actions follow the research," said Grace Packard from Voi.

As result, actions like Voi’s Gender Safe Parking Standard, which assesses accessibility, safety and wayfinding for e-scooter parking are important in prompting a wholesale shift where women’s mobility needs are entrenched in the design and delivery of services.

“This is not a silver bullet, but it is one of many things operators in the industry can do to provide an equitable public transport system,” added Packard.

However, what is critical here is, at the same time, both studies show how design, cost and marketing are equally neglecting the needs of those less physically abled, older and poorer. We see that not all women share the same sentiments about using these services, with age and wealth serving as principal factors shaping usage patterns.

This is not to say cities and public transport operators are not studying complex gendered mobility patterns, Catalonia, Transport for London and Umea (who helped shape the panel discussion) have conducted extensive research into women’s experiences; with Transport for London's research finding that LGBTQIA+ passengers are three times more likely to encounter unsolicited sexual behaviour on London's public transport compared to heterosexual people.

However, such intersectional data remains scarce. The FIA Foundation’s 2020 study, saw 93 per cent of respondents finding current data collection methods inadequate to make gender-inclusive transport decisions- let alone comprehend the compounding impacts of other factors.

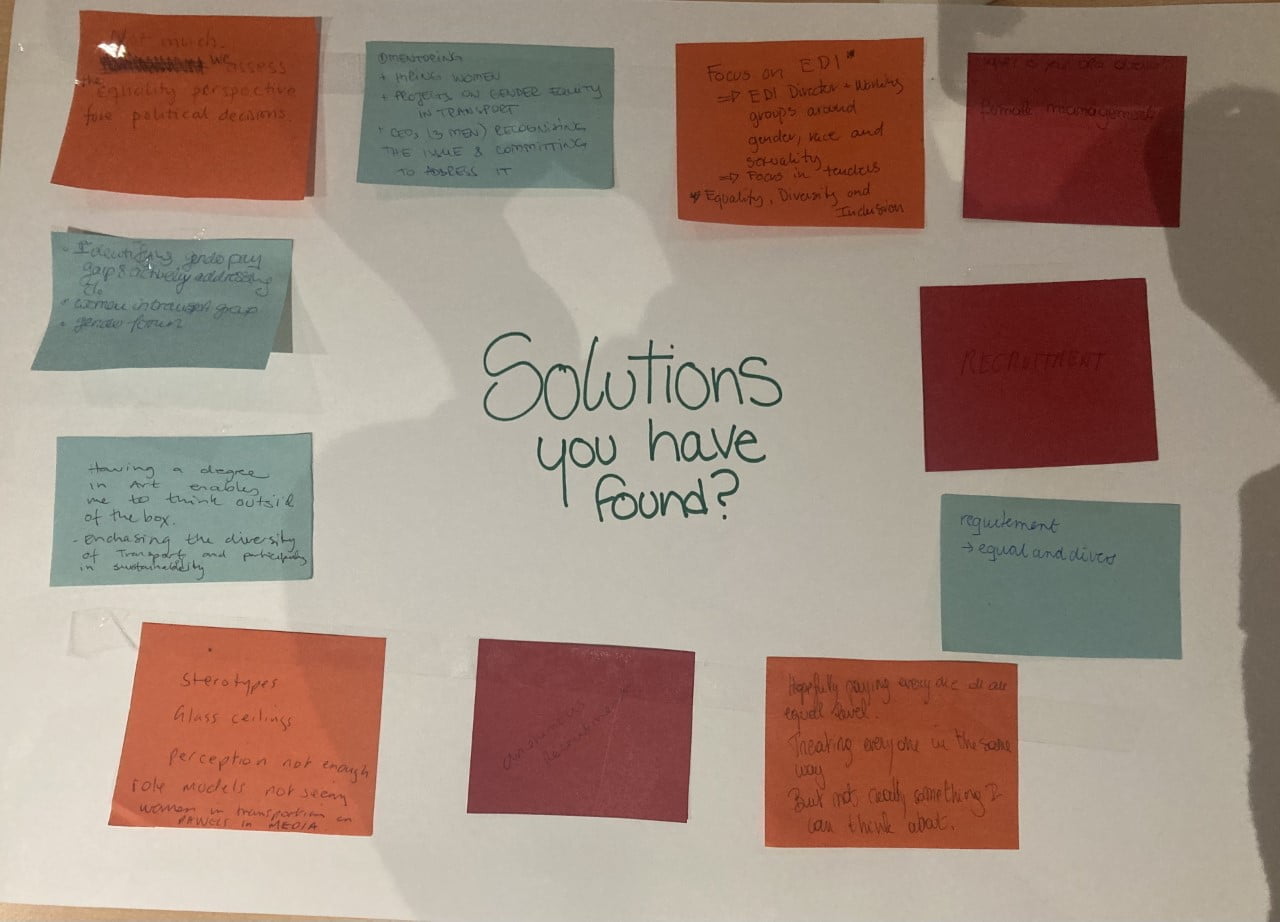

A collage from the workshop at the Annual Polis Conference, where the audience was encouraged to provide their insights

Women in transport - from user to decision maker

Creating a more focused and nuanced understanding of gendered mobility cannot- and will not- be achieved without more women in active and decision-making roles.

Women’s experiences as transport users and their role in decision-making are often treated as separate- or even antithetical- concerns. They are in fact two sides of the same coin.

Let's be clear, transport has a gender problem. Women account for just 22 per cent of Europe’s transport workforce. This is just an average – figures dip below 15 per cent in the bus sector and below five per cent of pilots. When you consider that women make up 47 per cent of the UK workforce, these figures are staggering – if not shocking.

At the same time women make up just 15.5 per cent of ministers with transport portfolios across the 27 EU Member States and one in five logistics organisations have no females on their boards.

In fact, the transport sector desperately needs more women. Staff shortages are stretching public transport and logistics to breaking point, while the urgency for innovation demands all the brainpower we can mobilise.

There are undoubtedly a range of initiatives to support women working in transport and encourage others to join.

For example, the Troopy Academy, an online learning platform designed and deployed by shared micromobility company, Troopy, provides resources for employees to help erode gender stereotypes and raise awareness of damaging practices.

Our Academy seeks to tackle gender inequalities, especially in mobility and transportation area; by providing learning materials we are supporting our employees in helping to make our organisation and the systems in place more equitable,” Troopy’s Francois Hoehlinger, told the conference panel.

This inclusive work environment plays out in the services we offer, enabling us to propose the correction on our vehicles that secures real inclusivity.

However, it is important to recognise there is no “catch-all” way of understanding women’s experiences working in the sector and the barriers they face.

An understanding of the role of race a socioeconomic background is key. The Race at Work survey, reveals significant differences between white women and their black, mixed race, Asian and Caribbean counterparts; not just in their labour market participation rates, but experiences of recruitment and employment.

This is especially true in senior leadership. According to Mckinsey’s report this year, only a quarter of C-suite leaders are women, and 1/20 is a woman of colour.

Redressing this imbalance with a focus on differences across the globe and the range of possible approaches is what the Sustainable Mobility for All Gender Working Group’s (SUM4All) latest initiative seeks to achieve.

The project – led by POLIS, a European network of cities and regions working towards sustainable mobility, with support from Heather Allen, an independent consultant with more than 25 years of international experience in gender, transport, sustainable development and climate change, and with funding from the FIA Foundation – will produce a practical guide to and toolkit for the essential changes which need to be made to secure greater female participation in the sector, based on good practice examples from across the globe.

Heather Allen presents the SUM4ALL project at the panel

Gender imbalance in the sector starts with recruitment and continues into employment, yet the data that we have does not allow us to understand the challenges that women face or to see where policies and initiatives could make a difference; this study looks to give us greater insights into where there has been changing and what still needs to be done.” asserts Heather Allen.

Indeed, preliminary findings from the survey reveal that, yes, a comprehensive shift in workplace culture is required, but not all actions work for all women, at all stages of their careers, with respondents revealing shared- but individual- experiences of working in transport. For example, support networks established to support women in the sector, can actually feel exclusionary for many.

As such, initiatives such as the Ambassadors for #DiversityInTransport network, which seeks to promote diversity, equality and inclusion in all its forms within the EU transport sector, by encouraging and supporting individuals and organisations in finding new ways to foster diversity will be critical.

“We urgently need to ensure that the needs of all transport workers and users are represented,” says Lucia Schlemmer, from Panteia who is leading this project.

Importantly, this programme seeks to attract individuals from across the sector with a range of backgrounds.

What is next?

This may throw a spanner in the works for those who want a straightforward understanding of gender, and unfortunately, there is ‘no quick fix’ for the challenges we face.

Nonetheless, it does reveal the importance of articulating exactly what we mean when we talk about “women’s issues” and use the language of “vulnerability”.

The conversation continues!

Interested in more on this topic, or have an initiative to share? Contact Isobel Duxfield at iduxfield@polisnetwork.eu