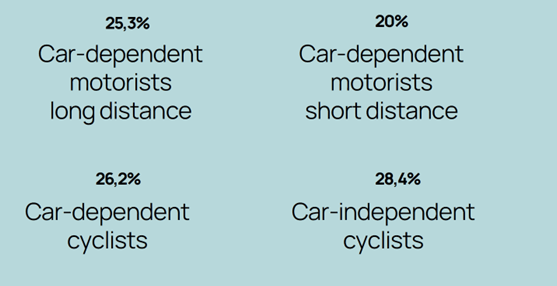

Access Just Transition Webinar: “That’s not feasible without a car"

POLIS' Just Transition Webinar series kicked off with a deep dive into car usage in cities, the why's, where's, how's... and what policymakers can do to shift car-oriented mindsets.

Nearly 1/3 of total urban greenhouse gas emissions in major cities are generated by transport, with air pollution responsible for over 300,000 deaths per year across the EU27. The race to carbon neutrality and decongestion is on.

London’s Ultra Low Emissions Zone, Brussels’ Good Move Regional Mobility Plan, Leuven’s Circulatieplan and Paris’ zone à faibles émissions mobilité: cities across the globe are hurrying to dethrone the personal passenger vehicle.

At a neighbourhood level, there is also a range of innovative approaches including, superblock development in Vitoria Gasteiz and Helmond’s Brainport Smart District - where locally led reallocation of space to prioritise active travel and public transport is changing mobility from the bottom up.

However, reducing car traffic from our cities is a complex process; as POLIS’ previous webinar investigating this issue revealed, there is a spectrum of factors underpinning car use, from age to occupation, childcare responsibilities to physical or cognitive capabilities.

Climate goals may be biting at our heels, nevertheless, efforts to cut carbon cannot overlook the impacts of our ambitious plans on those who depend on car travel.

A leading challenge for our cities and regions now is identifying different user needs, understanding individual relationships with car-centric mobility and pinpointing opportunities for shifting mindsets.

No average driver, no average trip

“That’s not feasible without a car.”

The pros and cons of urban vehicle access regulations are a much-rehearsed argument, and one which often involves impassioned exchanges. But what if there is a different way of looking at it? What if instead of rehashing polarising battles, we unpick what “car dependency” really means?

What are car-dependent places, dependent users and dependent practices?

To help traverse this complex topic, POLIS’ Just Transition Webinar elicited an expert on the topic, Eva Van Eenoo, to disentangle actual and perceived car dependence, and examine the opportunities for tailor-made interventions to reduce car use.

Eva Van Eenoo works at the research group Cosmopolis Centre for Urban Research (Vrije Universiteit Brussel), where she is investigating car-dependent places, people and practices.

Her research asks:

- How to define car dependency and how it can be measured?

- Is there a discrepancy between perceived car dependency by inhabitants of urban areas and actual car dependence?

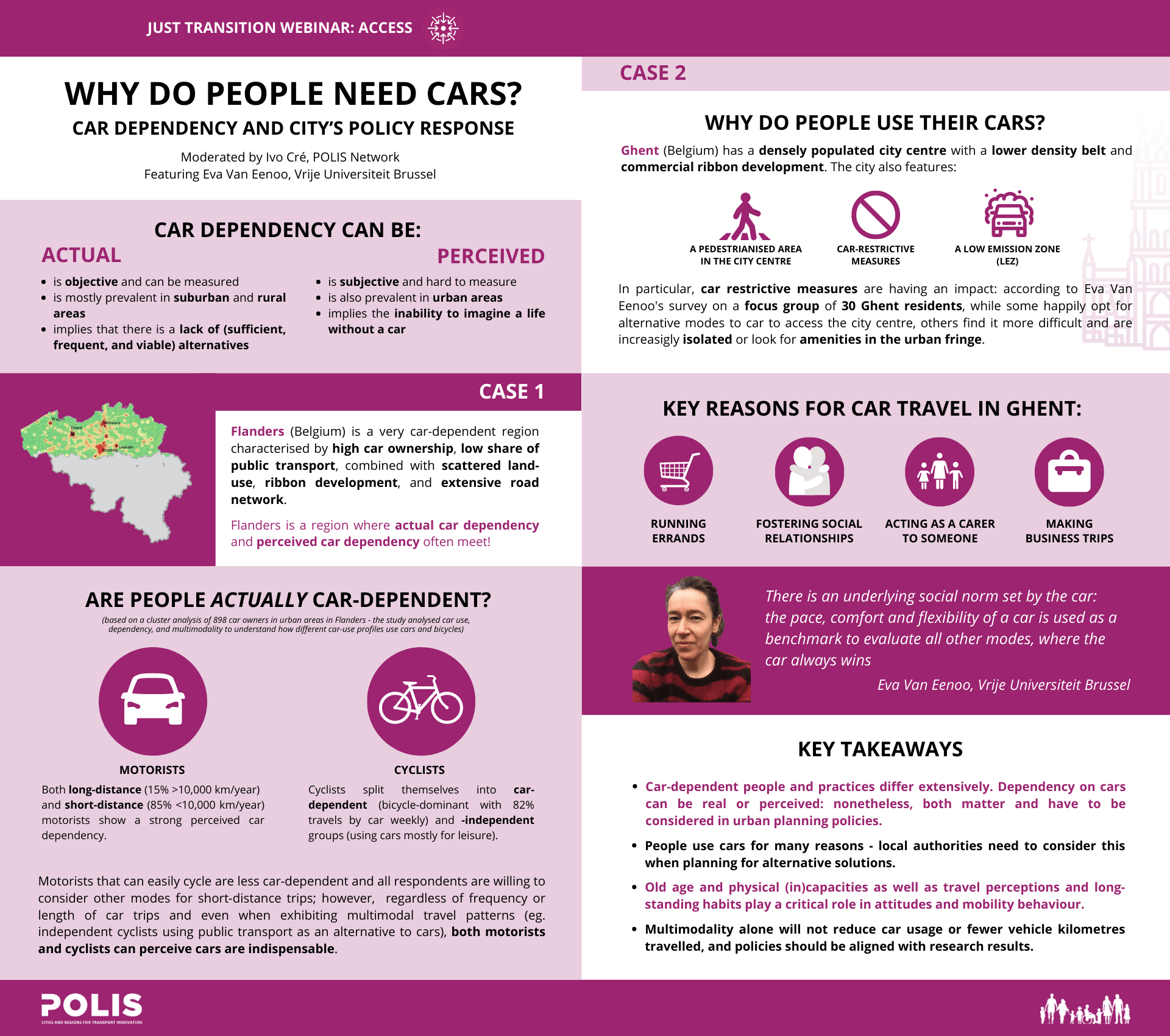

By mapping car-dependent regions based on several land use & transport characteristics and comparing these findings with the actual travel behaviour, Van Eenoo is exploring the extent to which accessibility and travel behaviour are shaping one another.

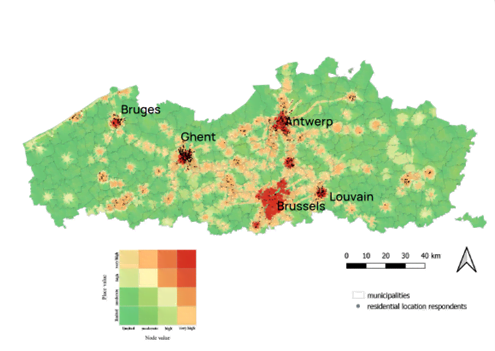

Van Eenoo performed a cluster analysis on data around car use, examining how different people in urban areas in Flanders use their cars, and bicycles and the number of kilometres travelled.

Her research revealed that differing perceptions of dependency were not necessarily directly akin to the length and duration of car usage. Groups travelling longer and shorter distances both saw themselves as “dependent” on their vehicles.

Research conclusions:

Car ownership does not necessarily induce perceived car dependence for people who can easily get around by bicycle. Regardless of the frequency or length of car trips and even when exhibiting multimodal travel patterns, people can perceive their car as indispensable. Perceived car dependence is not necessarily correlated with high VKT (vehicle kilometres travelled) or high frequency of car use.

Why do people use their cars?

Having deciphered the frequency of car usage, Van Eenoo then investigated WHY people use their cars. For this, she headed to Ghent. A city with 264,000 inhabitants, Ghent has a ‘historical’ city centre, which is densely populated, with a lower-density belt and commercial ribbon development.

Key reasons for car travel emerged:

- Cargo function- many respondents stated they used their cars multiple times a week to run errands. Many even asserted they had purchased their car to conduct this work.

- Social relationships- visiting friends and family was key, particularly for families with young children. Many saw their car as essential for their connection with others.

- Caring roles- fetching and carrying children to activities (particularly during the evening and on weekends), assisting older relatives.

- Work- business trips were seen by many as important. Even when some took the train for certain work trips, several regarded the car as indispensable to their work and careers.

There was acknowledgement that changes would need to be made without a car, which many may struggle with, and others were reluctant to do so.

The inability to ride a bike, lack of reliable and safe public transport, and fear of public spaces (especially at night) were noted as reasons for using a car.

“There is an underlying social norm set by the car, the pace, comfort and flexibility of a car is used as a benchmark to evaluate all other modes, where the car always wins in this case,” said Van Eenoo.

So, what does this mean for our cities? Recommendations for policy

“It is important to understand who to focus on, and what to focus on,” asserted Van Eenoo.

“There are groups which are less inclined to cycle- often lower income and older groups; these are also those who are likely to lose out financially from shifting traffic circulation and access plans.”

Van Eenoo called for a stronger urban planning policy to reduce urban sprawl, where less sustainable travel is more prevalent and encouraged by such dispersed inhabitation and amenities. She also highlighted that multimodality by itself will not lead to less car usage or fewer vehicle kilometres travelled, and policies should be aligned with research results.

“Multimodality is not a goal in itself,” she warned.

Key takeaways

- No one-size-fits-all: Car-dependent people and practices differ extensively

- The role of carsharing: Many car-dependent practices can be enacted and planned with car sharing; however, focus groups revealed a strong reluctance to use car sharing with fear of the inability to plan trips.

- Importance of age: old age & physical (in)capacities play a critical role in attitudes & mobility behaviour. However, Van Eenoo also described that this is also underpinned by travel perceptions, and reluctance to adapt long-standing habits

- Cities should not only consider their city centres but also intervene in fringe areas, as these induce a lot of car traffic. Urban planning and zoning are key in this respect.

Read the full report HERE.

About the Just Transition webinar series:

At the 2021 Annual POLIS Conference in Gothenburg, we launched the Just Transition Agenda.

At the 2021 Annual POLIS Conference in Gothenburg, we launched the Just Transition Agenda.

Urban mobility has to change substantively, to become cleaner and more resilient- this is no secret. However, affordability, safety, and inclusivity must be at the heart of this transition. A just transition in urban mobility ensures that the shift towards low-carbon mobility is equitable and beneficial to all members of society.

However, there is a long road (train track and bike lane) yet to travel.

Across several online events in February and March 2023, we traverse the multifaceted ways affordability, gender-related mobility patterns, age, cognitive capacities (and more), can guide the future of our cities and regions.

A truly Just Transition is one which addresses imbalance and unfairness across the entire mobility spectrum. Thus, each webinar launches an examination of mobility justice from a specific perspective, in accordance with POLIS’ different working groups.

From freight to parking, traffic efficiency to active travel, electromobility to safety- and everything in between- we begin to discuss how each sector has its part to play, the challenges ahead, and how cities and regions are treading new ground.