From paper to (de)pavement

Architect and urban planner Reena Mahajan discusses how pushing a stroller in Montevideo sparked a citywide movement for walkable streets, blending activism, design, and humour to address the interconnected challenges of mobility, water resilience, and community empowerment.

Interview with Reena Mahajan, eleborated by Alessia Giorgiutti.

POLIS: Reena, could you tell us a bit about your background?

Reena Mahajan: I am an architect and urban planner, and increasingly an advocate for walkable, regenerative cities. I am originally from India, where I studied architecture, but I have spent most of the past two decades based in France. Living and working in several countries has shaped how I think about cities.

Reena Mahajan: I am an architect and urban planner, and increasingly an advocate for walkable, regenerative cities. I am originally from India, where I studied architecture, but I have spent most of the past two decades based in France. Living and working in several countries has shaped how I think about cities.

My career began in architecture, but I soon became uneasy about designing isolated buildings for a privileged few. It felt disconnected from the broader urban context. That discomfort led me to urban planning: I wanted to engage with how cities actually function: how people move, live, and interact.

Over the past 15 years, I have worked with integrated urban planning agencies in France, leading large-scale projects like eco-district masterplans and public space strategies. But over time, I realised that even well-designed projects were not enough.

POLIS: What do you mean by that?

Mahajan: Even in ‘sustainable’ developments, we were reinforcing car dependency and sprawl. We had good intentions, but developers insisted on single-family homes with two-car garages, which went against the vision of creating more compact, walkable, and people-friendly neighbourhoods. As consultants, we had to deliver what clients wanted, and that was limiting. Policy and politics often overruled us, and I felt unable to speak openly about deeper cultural and systemic issues.

Eventually, I wanted to go further. I founded Studio Divercity, a platform combining urban design, creative advocacy, and public debate. It gave me the freedom to ask difficult questions and speak candidly.

POLIS: When did you start Studio Divercity?

Mahajan: Officially in 2020—it was dormant at first and has been fully active for about two or three years now. My guiding principle is simple: I want to replace car-centric sprawl with people-centred, nature-positive cities, through design, debate, and storytelling.

POLIS: When did mobility become such a central focus for you?

Proposal to transform Montevideo’s Rambla from a high-speed motorway to a multimodal boulevard, Reena Mahajan

with the support of Cecilia Olivieri, Juan Pablo Bianchi, Santiago Beiró, Tim Voßkämper

Mahajan: When I became a parent. I had always worked on mobility indirectly—shared streets, public space, collaborating with engineers—but I had never felt the consequences of car-centric planning until I had a stroller in my hands.

At the time, we were living in Montevideo, Uruguay. Navigating the city with a baby made the barriers brutally clear. While on maternity leave, I started a visual campaign called #MontevideoPacificada. Using photography, renderings, and infographics, I began challenging the dominance of cars in public space.

POLIS: What kinds of responses did you receive?

Mahajan: It sparked genuine debate. During that time, I joined the Women Mobilise Women Urban Leaders programme, which introduced me to the concept of the ‘mobility of care’—the idea that cities are still designed for the commuting male worker, not for the complex daily journeys of caregivers, especially women.

Caregivers rely heavily on public transport, often outside peak hours when services are less frequent. Add a stroller, an elderly parent, or a child on a scooter, and suddenly, the city becomes a minefield. I recall traffic lights timed only for cars. If you are slow, disabled, or with a child, even crossing the street becomes a risk. These experiences opened my eyes. I began looking at cities through the lens of children.

POLIS: What did you learn?

Mahajan: That cities are deeply adult-centric. Children are invisible in how we design public space. And yet, they learn through movement—especially in the early years. If a city restricts their ability to explore, we are limiting their development.

During the campaign, I was invited to speak in Parliament about child-friendly cities—not just playgrounds, but giving children the freedom to move safely. I often use this analogy: in the past, we protected children from wolves. Today, the threat is cars. But unlike wolves, we created this danger—so we can choose to fix it.

POLIS: What kinds of solutions did you propose?

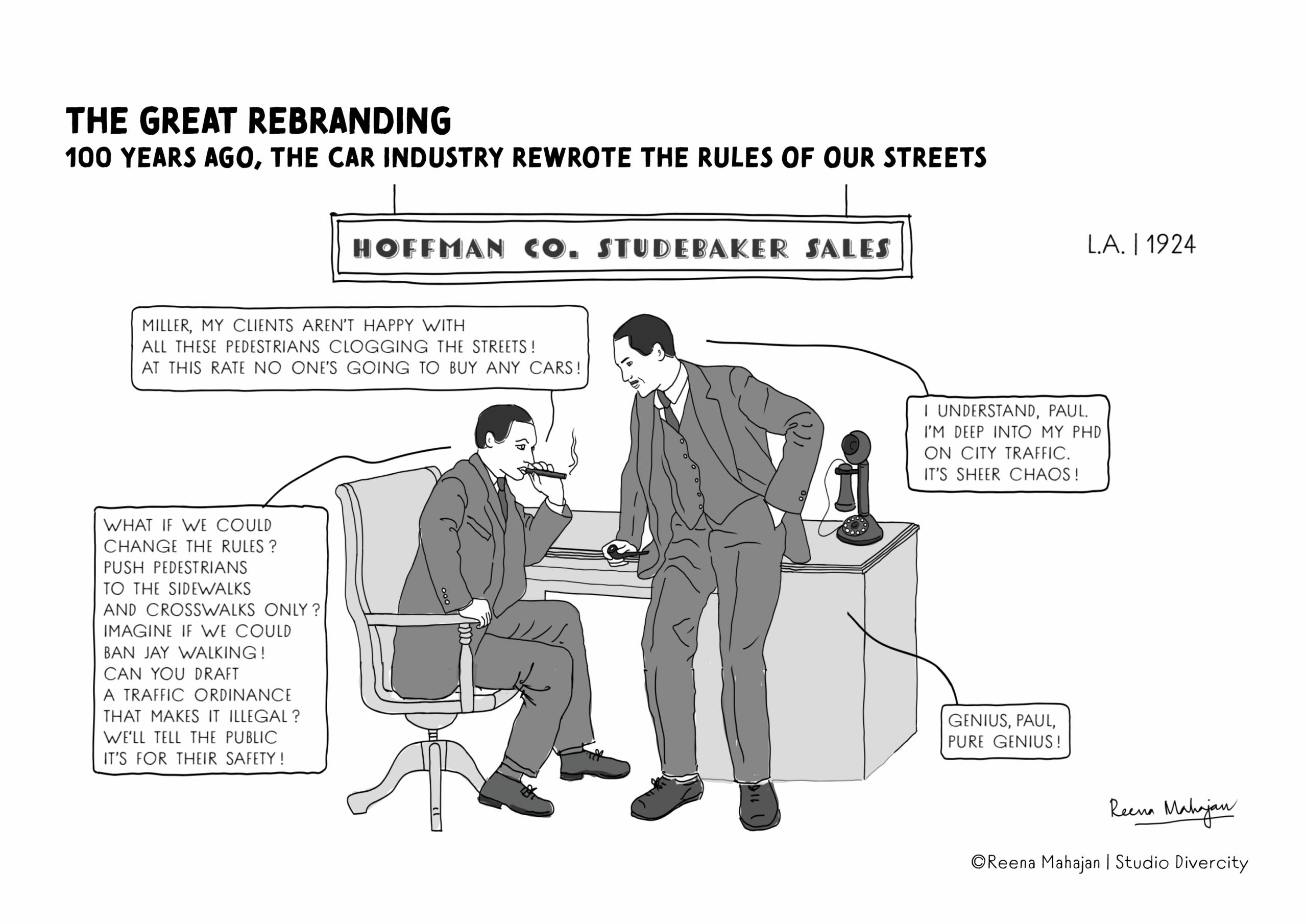

Mahajan: Visual storytelling was incredibly effective—especially cartoons. I would sketch on my iPad while out with my child. Using humour and simple drawings, I tackled myths about traffic and car culture.

Mahajan: Visual storytelling was incredibly effective—especially cartoons. I would sketch on my iPad while out with my child. Using humour and simple drawings, I tackled myths about traffic and car culture.

One time the Mobility Director at the City Council appeared on television, claiming bike lanes were ineffective because 'no one is using them.' When the interviewer suggested, 'Perhaps it’s because it’s too cold,' he responded, 'No, the problem is the heat.' They were blaming the weather, when in fact, the real barriers were clear: lack of cycling infrastructure, high speed limits and unsafe conditions.

In response, I created a cartoon showing the two of them in conversation, with a large elephant standing beside them—symbolising all the actual, unspoken issues. That became my way of engaging people: through satire and quiet humour.

It started on social media, where it resonated with people, and then it quickly grew beyond that. Journalists reached out. Some were sceptical—'Who is this foreign woman criticising our streets?’—but over time, my work gained traction because it was grounded in lived experience, backed by data, and offered practical solutions.

POLIS: Do you think your use of humour helped in softening the blow?

Advocacy cartoons that use satire and visual storytelling to highlight issues in urban mobility planning, Reena Mahajan

Mahajan: Absolutely. Facts alone rarely change minds. But humour, paired with personal stories and data, can make complex issues more approachable. I always tried to respond to criticism calmly and with empathy. Over time, even my harshest critics softened.

POLIS: Did any of this lead to concrete change?

Mahajan: Yes. Near the end of my time in Montevideo, the city built a cycle lane along the Rambla—a proposal I had campaigned for. At first, I was told it was unrealistic. Now it exists.

Paris experienced a similar transformation. When I arrived in 2006, it was far more car-oriented. Today, there are school streets, more urban greenery, and more women and children cycling. It is a major shift.

POLIS: Would you say the change in Montevideo was more bottom-up, while in Paris it came from the top?

Mahajan: Precisely. In Montevideo, it was a grassroots cultural shift—driven by artists, activists, and residents. In Paris, it was top-down. The mayor made bold policy decisions that then reshaped public behaviour.

POLIS: Talking about different cities, you have led and moderated workshops in Tiranaand Hyderabad with Les Ateliers de Cergy. Can you tell us more about it?

Mahajan: Les Ateliers has been facilitating interdisciplinary urban workshops for over 40 years. They bring together diverse groups—architects, urbanists, artists, economists, journalists—to work intensively with local authorities on specific challenges.

In Tirana, the focus was on urban resilience after the earthquakes—how to rebuild with long-term adaptability in mind. In Hyderabad, what began as a project on river corridor development evolved into a deeper exploration of river ecosystem regeneration.

Despite the different contexts, both workshops converged on one key theme: walkability. That is what I find so compelling—no matter the starting point, when you bring varied disciplines together, the solutions consistently return to human-scale, walkable environments. It is because walkability meets such a basic, often overlooked human need. It creates safer, more inclusive, and more liveable cities.

POLIS: Walkability is essential—but what about wheeling? How did disability or accessible mobility come into these discussions?

Mahajan: It absolutely came up, even if not always as a central focus. When I speak about walking and cycling, I also mean wheelchair users, carers, people with strollers—anyone moving through the city without a car.

POLIS: I am also interested in the case of Hyderabad. You mentioned the focus shifted from river corridor development to river ecosystem regeneration. Did that connect with your earlier work in water-sensitive urban design?

Mahajan: Very much so. Before focusing on mobility, my core work was about integrating water into urban design—not treating rainwater as a nuisance, but as a resource. At Atelier LD, where I worked for several years, every project began by reading the land—understanding topography, mapping natural flows, and placing water at the centre. From design to delivery, we worked with water’s natural path to bring added value to public space, including at the street scale, where we designed green infrastructure to restore permeability and resilience.

And really, walkability and water are closely linked. Car-centric cities tend to be paved, impermeable cities. When we bring nature-based solutions into streets—like tree cover and rain infiltration zones—we also make them more liveable, cooler, and socially vibrant. Streets make up 30% of urban land—they are as much climate infrastructure as transport corridors.

In Hyderabad, the project began with the river, but quickly expanded to the whole watershed. Hyderabad is a city of lakes, and we realised the river’s problems could not be solved without restoring those lakes. The river is, in essence, the sum of its parts.

But decentralised, nature-based solutions require neighbourhood-level involvement. What became clear was this: lose the lakes, and you lose the communities around them. To rebuild those ecosystems, you need connected, resilient communities—and that requires walkability.

So, even though the starting point was environmental, we ended up where I often do: at mobility. Preserving Hyderabad’s fine-grained network of local streets, improving the last mile, and protecting the human scale—all of that is essential to regenerating the river. It is all connected.

POLIS: Is there anything you would like to add in closing?

StreetSmart reveals the hidden design of streets to the everyday urbanist, Reena Mahajan

Mahajan: Yes — I am now exploring entrepreneurship. I am developing StreetSmart, a social impact startup focused on public engagement and climate action.

We are currently in private beta, developed with 15 volunteers from Climatebase, a global climate innovation fellowship. Our vision is to transform streets from spaces that endanger into places where people and nature can thrive together.

StreetSmart is a tool for citizen advocacy — helping communities and cities see what’s working, what is missing, and take action together to make streets safer, greener, and more liveable.

POLIS: What kind of data are you hoping to gather?

Mahajan: We are combining quantitative metrics with qualitative experiences. Most tools analyse cities from above—relying on maps and satellite data—we want to look at streets from eye level. To capture the lived experience: what people see, feel, and navigate every day.

We want to create a holistic view of liveability and help prioritise interventions. But technology must serve people—not replace them. The platform will rely on public input, not override it.

POLIS: It is good to hear that you are thinking about AI as a tool for public good.

Mahajan: Exactly. When I speak about reimagining streets, I do not just mean launching a polished app. The goal is real-world change. We need to move fast—climate change will not wait. Children will not wait 20 years to grow up because we need more time to fix what we broke. If we can plant a tree where there is asphalt today, we should not wait.

We are using AI to reveal what exists, not to render polished after-images. The goal is to support public imagination, not replace it—and to ensure the benefits of technology reach everyone, not just the tech-savvy or the well connected.

Click here to read the article in its original format.

About the contributors:

Interviewee: Reena Mahajan, Urban Planner & Walkability Advocate, Founder of Studio Divercity. Mahajan is an urban planner and advocate for walkable cities. Founder of Studio Divercity, she brings two decades of experience across three continents in sustainable urban design and water-sensitive planning. Based in Paris, she is currently building StreetSmart, a digital platform that combines data, design, and dialogue to reimagine streets and empower communities to shape liveable and climate-resilient cities.

Interviewer: Alessia Giorgiutti, Communications & Membership Lead & Co-Coordinator Just Transition, POLIS. Giorgiutti coordinates POLIS' corporate communications and magazine and has been involved in several EU-funded projects as a Communications Manager. She currently supports other managers and officers on tasks related to content production and communication for their projects. Her work focuses on making accessible and inclusive content about transport, as well as highlighting the experiences of marginalised users.

Street intersection repair proposal, Reena Mahajan

Street intersection repair proposal, Reena Mahajan