From listening to empowering: Ensuring women's safety in public transport

To make public transport an appealing and sustainable solution for all citizens, European cities must address the safety concerns of women. As part of its campaign for Women’s History Month, POLIS sat down with three advocates of a gender-inclusive approach to mobility innovation to discuss the obstacles that women currently face and identify possible solutions.

Women and transport

In 2021, the European Parliament authored a study titled ‘Women and transport,’ which revealed an appalling gap between men’s and women’s experiences of urban mobility. In particular, the study showed that:

- women’s travel behaviour is impacted by the risk of experiencing sexual harassment (Duchéne, 2011; Ortega et al., 2019);

- women perceive private transport as a safer mode of transport;

- current data on the frequency of sexual harassment in public transport, while already alarmingly high, likely provides only a conservative estimate of the phenomenon, given that many such incidents go unreported (Ortega et al., 2019);

- and that preventative measures, such as increased street lighting and the deployment of surveillance staff, can do much to enhance women’s safety, encouraging women to make use of public transport (Gardner et al., 2017; Chowdhury and van Wee, 2020).

With one half of Europe’s population excluded, directly or indirectly, from enjoying the benefits of public transport, cities across the region risk pushing for a mobility system that performs better on environmental indices but remains socially unsustainable. Addressing women’s safety concerns in public spaces is therefore a vital component of a socially equitable European Green Deal.

To find out more about the link between gender, security, and mobility, POLIS spoke to three individuals working on the frontlines of urban innovation. They helped us to identify the obstacles that women face in public spaces and assess solutions for a more equitable mobility system.

Re-owning public space

Susannah Walker, Co-founder, Make Space for Girls

As it turns out, women begin to face exclusion from public spaces at a young age. Even before public transport becomes a necessity for the daily activities of their adult lives, they find themselves in public spaces intended primarily for their male counterparts.

Susannah Walker confronted this issue head-on when she realised that her local council in England provided outdoor facilities for teenage boys but not for teenage girls. Outraged, she vowed to put the rights of girls and young women on the urban agenda, leading her to co-found the organisation Make Space for Girls.

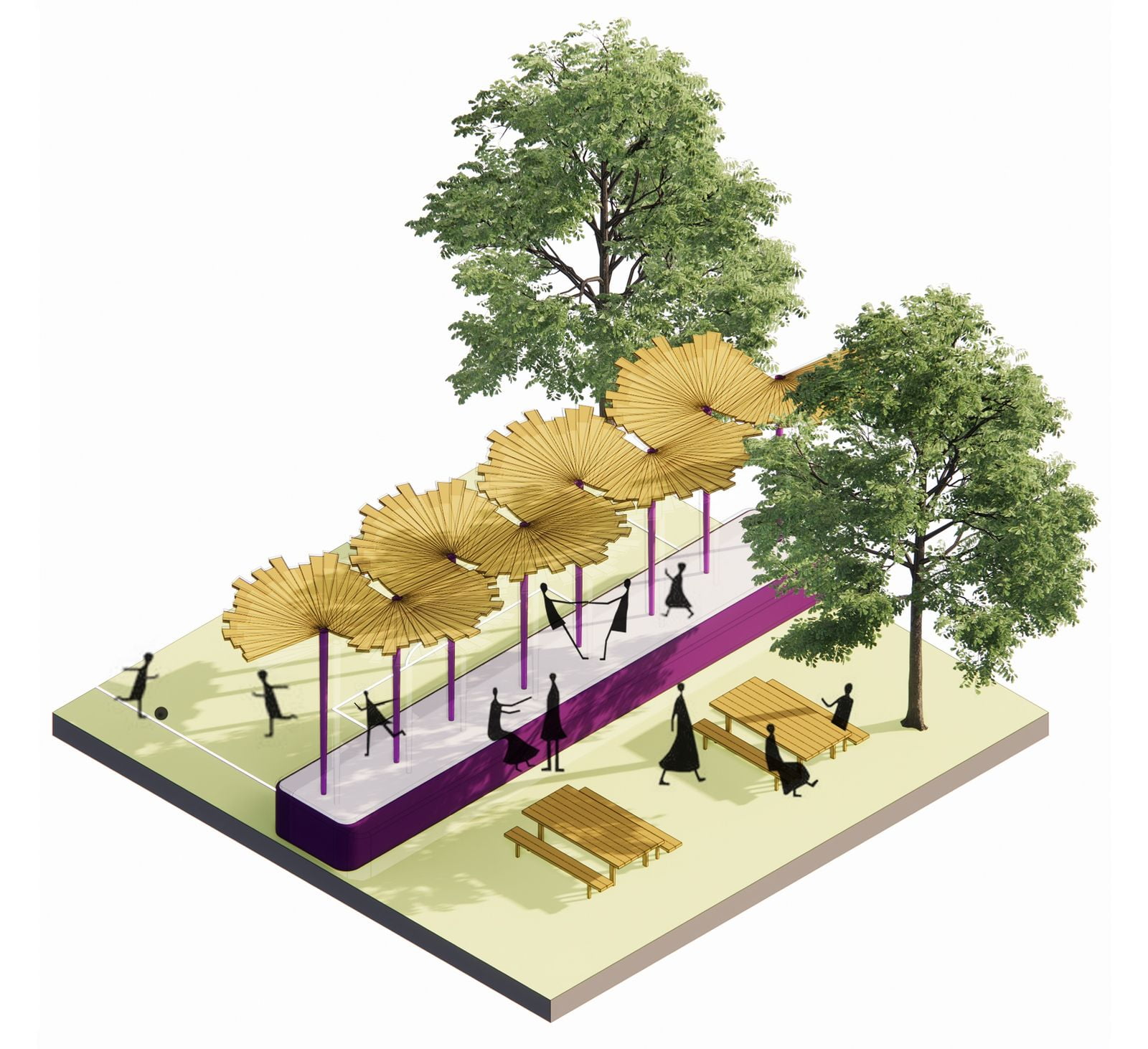

Reimagining outdoor spaces for girls. Credit: Make Space for Girls

“Make Space for Girls campaigns for better parks and public spaces for teenage girls and young women. Safety is one of the biggest barriers that prevents them from using these places. The biggest issue is a lack of awareness of this, and [the fact] that safety and gender mainstreaming are not written into many policies or plans.”

The first step in bringing about change, Susannah tells POLIS, was to make the public aware of the issue and collect data to support better decision-making. “Our Parkwatch campaign last year used a citizen science project to draw attention to the gender imbalance in teenage facilities. Measuring the problem is essential if we are to know what change works.”

One of the biggest challenges in mobilising young women to make use of outdoor spaces and public transport, Susannah explains, is eliminating the dangers that they face. “There does seem to be evidence now that it’s [the trip from] the doorstep to the stop or transport hub which represents the biggest safety issue, so we need to be thinking about street safety and design of the public realm to make public transport more accessible.

Safety, Susannah added, cannot be thought of as a simple add-on that urban planners incorporate at the end of a project.

“It’s a basic human right,” she tells us, “essential if half the population is to have access to public space. At the moment, however, much of the way we build things tells women and girls that they are meant to stay at home.”

Moving forward, Susannah would like to see more inclusion of girls and women in the design and management of public spaces. “We need to make sure that they are a significant part of the conversation, and that safety is foregrounded from the start.”

Putting our best foot forward

Jim Walker, Director, Walk21

For more than 20 years, the Walk21 Foundation has worked to shape more effective and inclusive pedestrian policies across Europe and abroad. Jim Walker, founder and director of the organisation, has made it his personal mission to enable citizens everywhere to enjoy their environment through walking. A large part of this, he tells POLIS, is about ensuring that everyone’s voice is heard in decisions about urban safety and accessibility.

“Women, children, the elderly, people with disabilities – everybody deserves to be asked about the extent to which the environment is supporting their needs,” he said.

Too often, however, urban planning is cast as an exclusive realm belonging to technicians, with little opportunity for broader societal engagement. “Despite its social, cultural and political dimensions, transport is framed as a technical issue that requires engineering and economic and technological skills and solutions. We tend to invest in is the engineering, the economics, and the tech, whereas we overlook the social considerations: gender and inclusion.”

Like Susannah, Jim argues that constructive dialogue is needed to bridge the gap between the urban policies that shape cities and the people who live in and use them every day.

“If you want the city to be relevant and supportive of women, then it's not just a single fix: it is about that particular, participative approach. We seem to have lost touch with having a relationship with people and making sure that what we provide is supportive and enabling.”

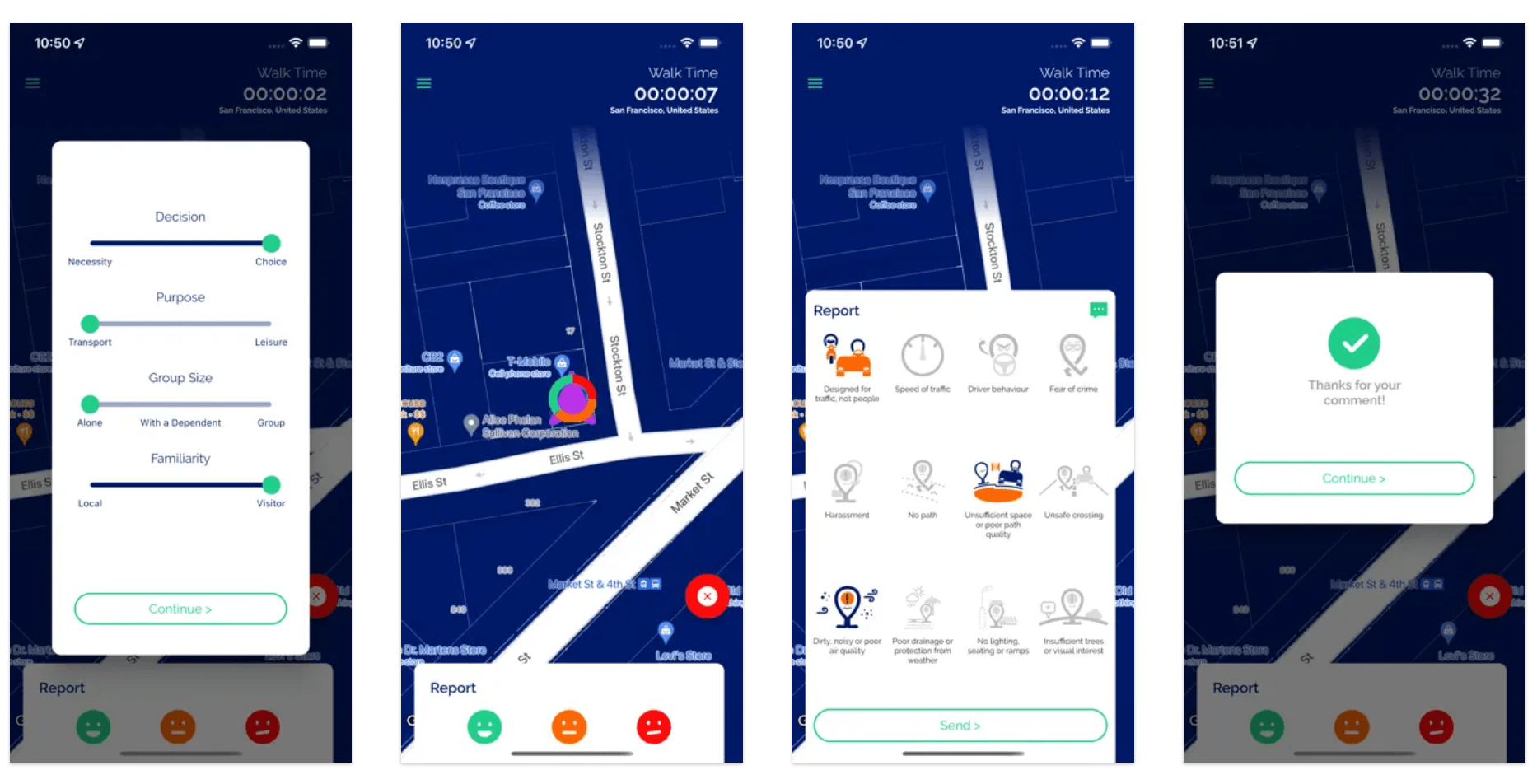

The Walkability.App enables citizens to share the reality of their walking experiences. Credit: Walk21

In an effort to fill this gap, the Walk21 Foundation has pioneered extensive research into pedestrian safety and launched a Walkability App, which collects data from city residents on the quality of their streets.

Giving urban communities the chance to voice their concerns, Jim explains, reveals much about the link between walkability and access to public transport.

“When you look at the research, 70 percent of the experience that people remember and particularly put a value on about their public transport experience is walking to or walking from the actual service itself. And if you think that 50 percent of public transport time is actually spent walking, and 90 percent of people accessing public transport are pedestrians, then we clearly need to be thinking about, well, ‘What is that walking experience like?’”

As highlighted by Susannah, pedestrian routes to and from transport hubs are a strategic point for safety interventions, especially when it comes to the safety of women. “Certainly, there are issues on public transport,” Jim acknowledged, “but let's not forget that the main issues we need to talk about are the design of stops and their accessibility, and making sure that the walk to and from public transport is of good quality.”

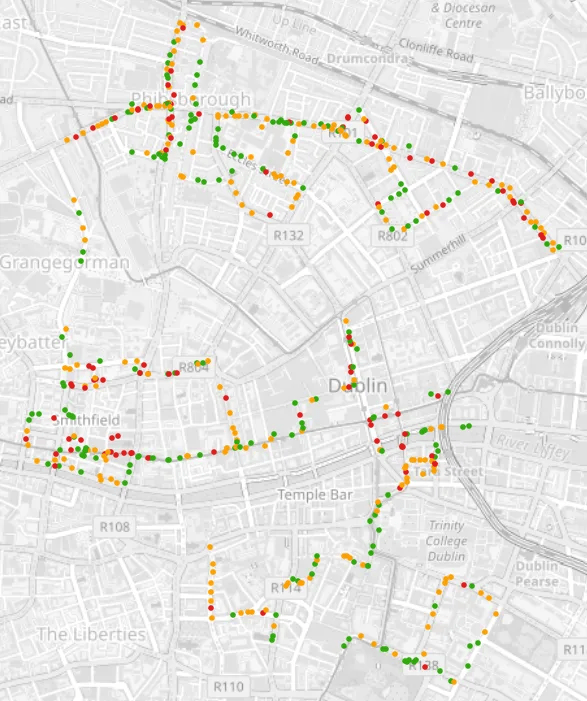

He highlighted Walk21’s past research in Dublin, where women were found to ‘motorise’ (i.e., give up on public transport, biking, or walking, in favour of private transport) more quickly than men. Upon investigating use of the city’s new Luas Light Rail System, Jim says, the local transport authority discovered that the rail line, though “designed brilliantly by engineers,” lacked appeal from the public’s standpoint.

Many of the points of access to the rail system, he explained, are located along “deserted corridors, which make people feel unsafe – not just women, but especially women.”

The Walkability app’s geo-located data set enables detailed walkability assessments. Credit: Walk21

Studies such as these are vital in understanding where and why women – and other citizens – feel unsafe when walking, biking, or using public transport. “We're realising that […] we can give people an opportunity to geolocate where they've got an issue and what they would like changed. Then we can look for clusters of concern. We can start auditing the environment in more specific places and we can target responses and keep using these tools to [monitor] interventions and understand the impact that they might have had.”

To fully enjoy the benefits of community-based science for urban mobility, however, women must feel that their feedback will be heard by local authorities and used to shape effective policies. “In lots of places, women don't expect to be asked, and they don't expect that if they did report something, anyone would listen to them or do anything about it.”

Without greater inclusion of women in the design of public transport and timely, comprehensive responses to women’s safety concerns, Jim warns, women will be left alone to develop solutions for themselves and other women. “We have to do it collectively, as a society, and we have to work out how we're going to make it better for all of us. […] It may be that we haven't solved everything overnight with just one change, but you know, if it's a constant conversation and an engagement with women.”

Encoding gender inclusivity

Sara Ortiz Escalante, Urban Planner and Sociologist, Col·lectiu Punt 6

Active since 2006 and formally established as a cooperative in 2015, the Barcelona-based organisation Col·lectiu Punt 6 is at the forefront of gender-inclusivity urbanism. Through urban planning and mobility project work, the organisation aims to insert an intersectional feminist perspective into the DNA of cities in Catalonia and abroad, with an emphasis on access, safety, and inclusivity for women of all backgrounds.

Sara Ortiz Escalante joined the collective in 2009. As a member, she has conducted gender audits, researched women’s safety in public spaces, and designed and facilitated trainings on gender-inclusive urban planning for local and regional governments.

Aerial view of Barcelona's coastline. Credit: Benjamín Gremler, Unsplash

The main challenge that Barcelona and other cities face, she tells POLIS, “is that cities have been built and planned from a male-centric, patriarchal, capitalist perspective – that is, thinking from the perspective often attributed to a middle-class white man with a full-time job and all his abilities.”

As a result, she explains, “architecture, urbanism, and mobility are planned with the ‘typical male citizen’ in mind, which, deep down, does not reflect the reality of our cities. Women represent 51 percent of the population, in all our diversity, and if we also consider children, older people, and other people who do make the profile of the ‘typical male citizen’, we realise that the city has excluded many of us.”

Consideration of women’s diverse mobility needs, she says, is lacking, which in turn increases the feeling of unsafety that many women experience on public transport.

“I think […] our understanding of urban security is entrenched in a capitalist, neoliberal vision, where it is understood, without doing a gender and feminist analysis, that security simply means putting more police or more security cameras in public transport. But we have been documenting for years that more cameras do not prevent sexual assault or harassment or verbal harassment. They can document it, but this doesn’t necessarily give women a greater sense of safety.”

The situation is only made worse by the fact that women in Barcelona are the primary users of public transport, and therefore depend on a male-dominated sector to plan for their needs. “In some of Barcelona’s public transport systems,” Sara explains, “women represent 70 percent of users. In other words, seven out of ten people who travel by bus or metro, for example, are women. Our intensive use of public transport gives us opportunities to access certain places, but on the other hand, it also has an impact on some other social elements that are fed by this patriarchal [vision] of mobility and architecture.”

A lone female passenger in Barcelona's public transport. Credit: Pere Jurado, Unsplash

According to Sara, gender-based violence is far from a rare occurrence in Barcelona’s public transport system. “A recent survey released by the province of Barcelona in 2020 revealed that more than 50 percent, almost 60 percent of women using public transport had suffered or experienced some situation of sexual harassment, or for gender reasons while travelling in public transport, mostly in the form of comments, insinuations, is invasions of personal space. And this percentage was much higher among younger women between the ages of 16 and 25. More than 90 percent of them had experienced sexual harassment of some kind while using public transport.”

Contextualising gender-based violence, Sara adds, requires awareness of the intersections between sexism and other forms of discriminatory behaviour. “Many times, sexist violence is linked to racism, ableism, fat phobia, and other forms of violence. We cannot carry out a comprehensive analysis of security in public transport from a gender perspective without also integrating this intersectional perspective.”

To combat gender-based violence of all kinds, Sara’s organisation has been working on tools for transport system analysis and auditing. “We have also integrated this [perspective] into mobility guides, where we define different gender criteria that should be considered when planning mobility.”

With an emphasis on gathering qualitative data through surveys and interviews with women, such as nocturnas – female night workers in Barcelona – Col·lectiu Punt 6 is helping to bring women’s voices into the mobility debate. Even so, Sara recognises that much more is needed. “We understand that our organisation’s work must be supported by a systemic transformation in various sectors, from education to the workplace, if we really want to create cities free from gender-based violence,” she tells POLIS.

In the future, Sara is hopeful that innovative efforts like those being undertaken by Col·lectiu Punt 6 can be gain traction across the mobility sector. “Some initiatives are being carried out, such as ‘demand stop’ services – asking the driver to stop between two official stops in the night bus service for women and minors to reduce the distance between the stop and their destination. Is this going to eliminate gender-based violence? No, but it is going to enhance women’s comfort and perception of safety.”

To ensure that future research into gender-equal mobility and women’s safety in public spaces leads to concrete actions, Sara agrees with Susannah and Jim that urban planners and policymakers will need to make it inclusivity one of their organisational objectives.

What the transport workforce 'looks like' to many. Credit: Jack Lucas Smith, Unsplash

“Many times, those of us working on these issues are neglected and infantilised. The fact of putting feminism in the centre – focusing on care, gender diversity, etc. – has often been read as something that did not apply to planning or mobility, something that was not essential. […] There need to be protocols to ensure that transport providers are making it one of their priorities to eradicate gender-based violence in public transport.”

Moreover, she believes that women themselves should be at the helm of change-making, not only as study participants, but also as the leaders of tomorrow’s transport systems. Considering that women currently make up only 22 percent of the transport workforce, Sara says, “[they] need to be better represented across the entire public transport network – as drivers and as managers.”

These changes, she says, will be imperative if Europe cities are to “obtain data that approximate the reality of [public] transport and move beyond the ‘male’ model of urban planning that we have always relied upon, integrating a new diversity of mobility concerns, needs, and desires.”

By making gender a central component of urban mobility planning, Sara concludes, “we can move toward a society that invests much more in infrastructure, public transport, and modes of active travel that are sustainable and inclusive, rather than investing our efforts in something that serves only a small group of people.”

Listening, responding, and empowering

From our discussions with Susannah, Jim, and Sara, POLIS was able to contextualise women’s feelings of unsafety in public transport and public spaces. Their work on inclusive mobility in different cities both within and outside of Europe complements a growing consensus that urban environments, which have historically been designed by and for men, consistently fail to account for the diverse mobility needs of women. Moreover, it reveals that an intersectional perspective on gender-based violence in public spaces is needed to eliminate the threats that women face.

All three interviewees lead the work of organisations committed to shining a light on women’s experiences of public transport and public spaces. Their common goal is to ensure that female residents are better represented in qualitative and quantitative studies of street safety and transport accessibility. Through their work, they seek to provide mobility planners with new opportunities to hear and learn from women.

Just as important as giving women a voice in studies on gender, security, and transport, however, are efforts to integrate women into a male-dominated transport sector. For women to fully enjoy the benefits of public transport, interviewees agreed, they must be active participants in the decision-making process that shapes cities. Only by empowering women to join the table will Europe’s cities succeed in achieving sustainable mobility outcomes that work for all.