The Lifecycle Of An Assumption

Sustrans and Arup are on the cusp of publishing a report that focuses on the importance of inclusivity in cycling. Five members of the project team, Mei-Yee Man Oram, Susan Claris, Jasmine O’Garro, Tim Burns and Andy Cope, present some significant early findings.

Cycling has the potential to improve our health, air quality and congestion, which can make our cities more attractive and liveable.

Bike Life, the largest assessment of cycling in cities and towns in the UK showed in 2019 that 58% of residents would like to see more government spending on cycling [1]. Currently 83% of residents in Bike Life cities walk at least once a week; when we look at cycling, this drops significantly to only 15%.

Despite the obvious value to health and wellbeing of our communities and our environment, the full value that cycling offers is not being realised. Currently, the highest levels of cycling in the UK are observed among white males aged between 17 and 49 [2]. Why is this? What groups of people are currently not cycling and what are the reasons for this?

Stage 1 Inclusive Cycling in Cities and Towns report. Photo Sustrans

Several intersecting groups are under-represented in this cycling community, namely women, older people (65+ years), disabled people and people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups (BAME) as well as people from lower socio-economic backgrounds. As part of a joint study by Arup and Sustrans, we have looked to highlight the barriers and identify opportunities for making cycling a more inclusive activity.

More than a cycle

As well as the convenience, cycling can also be highly beneficial to an individual’s health (through active travel and exercise) and health for other people (due to better air quality), as well as having economic benefits (for example, enabling access to employment and services) The greatest benefits of cycling can be achieved if it is inclusive and accessible, and meets the needs of the wide range of people that live in cities and towns. Having inclusive modes of transportation allows people to contribute, participate and be included in society. With the current global Covid-19 pandemic, the positive impact that cycling has had on mental health and wellbeing is clear – with Sustrans, British Cycling [3] and Cycling UK [4] offering advice for those wanting to start or continue cycling for leisure or essential travel. Cycling in this period is being used as an alternative to travel on public transport for key workers. Because of these reasons cycle shops have been allowed to remain open for purchase, repairs and maintenance.

Current issues in inclusive cycling

Most urban areas are designed around car usage, which can make active travel (including walking and cycling) difficult for many people. Increasing inclusivity in cycling can open doors for people and can help to increase the mobility of people who live and work in urbanised areas. Implementing measures to make cycling a more normalised, enjoyable and safe activity could inherently reduce inequalities, increase mobility and promote a healthy lifestyle all whilst contributing to being environmentally friendly.

In comparison to other forms of transport, cycling in the UK is not as widespread as it is in some other countries – for example Denmark and the Netherlands. Through consultation and focus groups, as well as exploring lessons learned from our European neighbours, we have been able to identify barriers to cycling under the following three categories:

Increasing inclusivity in cycling helps to increase the mobility of people who live and work in urbanised areas.

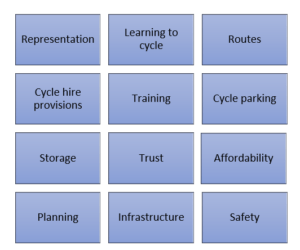

- Supporting People to Cycle

- Improving Places

- Better Governance

Analysis of Sustrans’ Bike Life 2019 data collated in 13 cities across the UK found that there are five under-represented groups in cycling:

- Women

- BAME backgrounds

- Disabled people

- Older people (65+ years)

- Lower socio-economic backgrounds

Supporting people to cycle

“There is a need for more role models and champions in cycling that are everyday people” – London stakeholder workshop participant

The term ‘cyclist’ for many is associated with a certain type of person and very specific characteristics (non-disabled, white, middle or upper class men). 19% of people from lower socio-economic groups stated that they did not think cycling was for people like them [5], and did not identify with the presumed characteristics of a ‘cyclist’. There is also a perception that cycling is ‘a sport’, rather than an everyday activity for travel.

Barriers people face in cycling

There are items that have been raised as barriers that impact the identified under-represented groups specifically – for example:

- Women – there is a perception that cycling is not feminine, and culturally there is still an expectation for women to meet physical appearance and cisgender expectations.

- BAME backgrounds – there are generally low cycling participation rates from people of ethnic minorities, and there are several reasons that may contribute to this: for some cultures, travel choice is associated with wealth, and thus it may be more aspirational to own and travel by car than cycle.

- Disabled people and older people - 9% of people who cycle weekly identify as disabled [1]. There is a large crossover between older people and disabled people; 45% of pension age adults are disabled [6]. Barriers for disabled people include confidence in safety and the anxiety associated with this.

- Lower socio-economic backgrounds - main concerns within lower socio-economic groups relate to safety, confidence in cycling and the cost of a suitable cycle.

Despite some of these specific barriers for each under-represented group, there are several that are common across all groups. These include safety (personal safety, and safety relating to sharing the road with vehicles), confidence, worries about cycling alongside experienced cyclists/commuters, and not identifying as a ‘cyclist’. Barriers can affect people’s confidence to travel, especially during busy or crowded times. At their worst, barriers can push people to stay at home and not travel at all. Representation is also a big factor, common across the different groups, with cycling in the media often represented by little other than young, white and affluent men. Non-sport leisure cycling is often portrayed negatively in the media, highlighting road traffic collisions, bad behaviour, or association with youth crime, which may deter some people from participation through fear of personal safety or through worry of other people’s perceptions of them.

Improving the diversity of representation (ability, age, gender, ethnic and economic background) in the media could be beneficial, giving those who may be interested but don’t feel they fit the ‘mould’ the opportunity to have people to look up to that they can relate to. Another way to overcome this barrier is training sessions and learn-to-cycle initiatives geared around leisure, socialising or general activity – removing the sporting connotations that may be off-putting for some. An example of cycling initiatives focused on people have included ‘This Girl Can’, organised bike rides to build confidence and socialise, ‘London’s Cycle Confident scheme’ that provides free cycle training sessions across London, and ‘Wheels for Wellbeing’, an inclusive cycling programme with adapted cycle sessions.

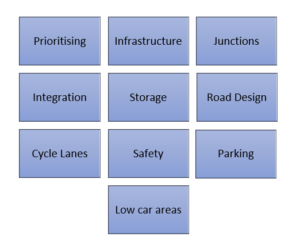

Improving Places

“I’d like to see poorer neighbourhoods prioritised for cycle infrastructure. In my ward 51% of people don’t have a car. There have been public transport cuts too – it’s really isolating. Access to bikes and cycle infrastructure could provide social mobility and improve health.” – Bike Life 2019 participant.

Key barriers in infrastructure when cycling

The built environment is important in ensuring people feel safe when cycling, with opportunities (if designed well) to support different levels of participation and confidence, including balancing the requirements of different road users. Concern relating to safety, which has been common throughout our discussions with the focus groups, has resulted in exploration of solutions relating to dedicated space that is physically separated and protected from car traffic and separated from pedestrian walking areas. Some 77% of people agreed that having more cycle tracks that are physically separated from traffic would be useful to help encourage higher levels of cycling activity [6]. Other barriers included lack of connections with other forms of transport, including sufficient cycle parking at train stations, where there may only be one cycle parking space for every 52 passengers at railway stations [7].

Developing a dense network of protected cycle routes across urban areas, supported by off-road routes and routes on quiet streets, should be a priority. Routes need to be attractive, fully accessible, and make users feel safe and secure.

On local streets where space may not allow for delineated routes, other measures can be introduced to readdress the balance between different road users, including reducing car volumes and travel speeds to create zones that prioritise people over vehicles. Continuity is an important facet of effective cycle-friendly infrastructure. Traveling into and out of city centres and commuter belts and going beyond to create networks for cycling that link up places where people live with everyday destinations across our cities and towns benefit all users, but are particularly helpful for less confident groups. As well as the routes themselves, the supporting facilities need to also be integral to this approach. This should consider secure and safe cycle parking and storage that is fully accessible for all types of cycles, not just two wheeled cycles. Such initiatives are demonstrated in Waltham Forest where there are seven hubs at railway stations, 600 spaces, and 20 spaces for cargo/adapted cycles.

Representation played an important part under the ‘supporting people to cycle’ section and reveals itself here as well under ‘places’. Consultations on infrastructure improvements and route planning should be more representative. Using citizen’s assemblies or focus groups allows a more representative sample of people to explore solutions and to allow non-expert end users to have their say.

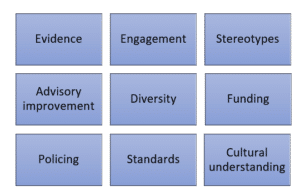

Better Governance

“National governments across the UK recognise the importance of more inclusive cycling … However, there is little information about how governments seek to deliver this” – Stage 1 report [8]

Key barriers in governance and policy when cycling

People are at the centre of making cycling more inclusive. Infrastructure, initiatives and governance can only be as innovative and inclusive as the people who are part of policy development. For example, respondents to the Department for Transport’s Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy (CWIS) Safety Consultation in 2018 consisted of 24% women in comparison to 75% men, and only 5% self-identified as disabled (in comparison to 20% of the UK population). 86% of the respondents indicated that they cycle at least once a week. Overall, only 15% of UK residents in cities and towns (1) cycle once a week, and without conscious efforts to diversify the input into designing for cycling, there is a risk that we will only improve conditions for people who already cycle, but not address concerns from those that do not cycle but would like to (thus increasing uptake in the long term).

Generally, barriers include a lack of leadership and ambition to make cities better for cycling, the omission of cycling in transport strategy, or little financial support around cycling. More group-specific concerns raised included worries about reduced or withdrawn benefits as a result of being physically active (from disabled people), and concerns of increased harassment by the police (from BAME communities). To design appropriately for all users requires a much more conscious approach to understanding what can be done to design spaces to encourage use by diverse groups. The design of these spaces can contribute to wider global initiatives, such as the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), contributing to a fairer and more sustainable future for everyone. Again, representation is a key issue here. We need to ensure that views of underrepresented groups are actively sought in political processes, policy development and transport planning. Ensuring that underrepresented groups are adequately represented and can relate to the policies, strategies, campaigns and initiatives, will develop a culture of everyday cycling that is inclusive and welcoming for all people.

What’s next?

Arup and Sustrans are currently in the process of analysing data from our most recent workshops, and this article serves as a precursor to forthcoming guidance to inform policy and make cycling truly inclusive and enjoyable for all. This report will be published in Summer 2020.

Authors: Mei-Yee Man Oram is UK Access and Inclusion Lead, Arup. Susan Claris is Associate Director, Transport Consulting, Arup. Jasmine O’Garro is Access and Inclusion Consultant, Arup. Tim Burns is Senior Policy and Partnerships Advisor, Sustrans. Andy Cope is Director of Insight, Sustrans

References:

[1] Bike Life 2019 report https://www.sustrans.org.uk/media/5942/bikelife19_aggregatedreport.pdf [2] UK cycling statistics: DfT, 2018. Walking and Cycling Statistics, England: 2017 [3] COVID-19 FAQ’s https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/about/article/20200319-about-bc-news-Coronavirus-Covid-19-FAQs-0 [4] Cycling and COVID-19 https://www.cyclinguk.org/press-release/cycling-uk-advice-families-continuing-ride-during-covid-19-outbreak [5] The UK population is ageing https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/august2019#the-uks-population-is-ageing [6] Family Resources Survey: financial year 2016/17 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-resources-survey-financial-year-201617 [7] DfT, 2018. Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy (CWIS) safety review – Summary of responses. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/748760/summary-of-responses-cwis-safety-review-call-for-evidence.pdf [8] Stage 1 report: https://www.sustrans.org.uk/media/1029/1029.pdf

Case studies:

This Girl Can: https://www.thisgirlcan.co.uk/activities/cycling/

Wheels for Wellbeing: https://wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk/

Cycle Confident: https://www.cycleconfident.com/

Waltham Forest : https://www.walthamforest.gov.uk/content/cycle-security-cycle-hubs-and-bikehangarss

The lifecycle of an assumption

The lifecycle of an assumption