School Run of Fun

Explore how Turku, Finland, is revolutionising school travel to enhance children's well-being, learning capabilities, and environmental sustainability. Discover their holistic approach to foster cycling skills, motivate parents and kids, and create a culture of active and sustainable mobility from an early age.

To listen to the recording of the article below, please accept all cookies.

Turku, Finland, is turning a new leaf with the groundbreaking Horizon 2020 SCALE-UP project — an innovative effort that is all about reimagining how kids get to school and kindergarten.

By promoting sustainable and active mobility, the city is not only working towards its 2029 climate neutrality goal, but also improving children and parents’ health and learning. This shift in mobility is not just a local change, but it is a city-wide and cross-cutting effort connecting several administrative levels. After a successful test run from 2022 to 2023 in six educational units, the so-called activation model is now expanding to five more, revolutionising the way Turku’s families do the school run.

Where to start

According to a yearly national health promotion study, only 42.6% of children in Turku in 5th grade report meeting daily physical activity recommendations. Additionally, when it comes to school trips in pilot schools, just 51.96 % of students are using active modes of transport, and 15 % opt for the bus.

Daycare children on a traffic adventure with the bicyclebus e-cargo bike. Credit: City of Turku

For parents who take the car, the median distance to the school is 1.5 km, and the primary reasons reported for them to drive are weather-related, being in a hurry, or convenience. Surprisingly, none of the respondents mentioned safety as a concern, which suggests that car users might be underrepresented in the survey, as this reason has been frequently brought up by parents.

Within the SCALE-UP holistic activation model, all sustainable transport modes are being promoted, but cycling is getting some extra attention, as we are more and more learning that the ability to cycle can no longer be taken for granted.

Recent research shows that children in Finland learn to cycle at the age of 4.8 (Cordovil et al. 2022), but what the research does not say, is how polarised the phenomenon is. During the planning process, the research team learned that there are schools and areas in Turku where many children are unable to cycle, with skill levels varying a lot among those who could — In collaboration with Turku University of Applied Sciences, a cycling skills test was conducted twice on a dedicated track adapted from the studies of Ducheyne et al (2013) and Papanikolaou & Adamakis (2020) to objectively measure the cycling skill levels of 257 children based on seven subskills/tasks.

Awareness raising, skill development, and joy of everyday movement

Throughout the planning process of the activation model, several key questions emerged:

- Are children capable of safely cycling in traffic or do parents have the skill and will to teach and encourage their children to walk or cycle to school?

- Do families, friends, and friends of families offer social support for choosing a bike or bus instead of a car?

- Do all children have access to bicycles, or do our physical surroundings facilitate safe and pleasant active trips to daycares and schools?

- Are we encouraging citizens to choose the potentially more time-consuming or more physically effort-demanding alternatives of travelling?

- Perhaps most importantly, do people stop to think about their daily habits and choices for commuting?

These questions stem from the COM-B-model (Michie, van Stralen, & West 2011), which is widely used in the planning of health behaviour interventions, hereby adapted to the context of mobility. According to this model, for a targeted behaviour to occur, one must have (1) (physical and psychological) capabilities, (2) (social and physical) opportunities, and (3) motivation.

A model for all children

During the scaling-up phase of the model, efficiency, with limited employee resources, became a priority. For daycares, the focus was raising awareness among personnel and parents, along with providing kick bikes, children’s bikes, and other cycle services.

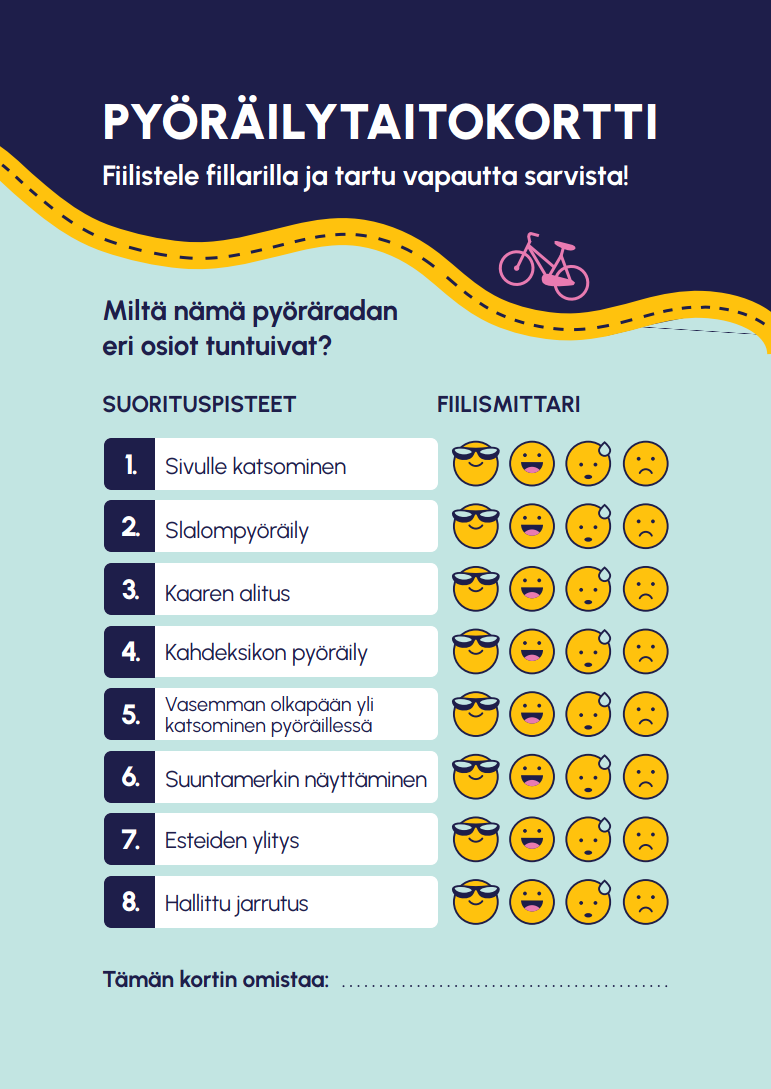

Skills card for cycling with all the provided measurement points. Credit: City of Turku

Information on the development of cycling skills, the importance of everyday movement, and available services was offered through handouts and healthcare channels, as well as at events held at daycares. Also, giving children a chance to be heard in the process allowed them to transform the narrative and perspective on their daily trip to daycare from a routine chore to an exciting adventure.

In the pre-school year and up until 3rd grade, parents proved to increasingly be thinking about various and alternative travel methods to school, emphasising safe traffic skills, the relevance of active travel for learning, and overall health. Children received worksheets that took into account their neighbourhood’s built environment, and discussions with parents on safe and sustainable school trips were conducted at parents’ events.

With older children, Turku’s model showed that the emphasis should shift towards motivating them to actively travel. Moreover, not only do children need motivation, but also the parents need reassurance and tools to motivate them to embrace active mobility. Within the frame of the project, a two-week nudge campaign yielded positive results, increasing peer support even among 6th graders and inspiring school personnel to opt for more sustainable modes for commuting, too.

Moreover, cycling services were extended to all participating units, with city employment services handling bike delivery and bike rotation to schools when needed, as well as maintenance, and in collaboration with Turku’s sports services, cycling lessons were incorporated into schooldays and teachers were encouraged to use bikes in schools.

Additionally, within the already mentioned cycling skills test conducted in collaboration with Turku University of Applied Sciences, individual scores were not disclosed to families, but children were provided with a skills card to self-assess their perceptions of the measured subskills, emphasising knowledge enhancement and cultivating positive feelings towards cycling. The card included training tips and a diary, encouraging children to share their progress with parents, who also received detailed descriptions of the subskills and their importance.

During the subsequent training period, children engaged in either independent training or structured lessons, with the initiative concluding with a repetition of the skills test and a post-cycling questionnaire, gauging enthusiasm toward cycling and evaluating the impact of the track, skills card, and training on the participants' overall engagement and lesson participation.

Scaling up

Final results, such as the effects of this model on the modal split, will be analysed by the end of 2023.

However, results regarding cycling skills and feedback from personnel and parents are already promising. During the process, parents have gained knowledge of different aspects of the skill of cycling as well as the confidence to allow their children to cycle. Instead of focusing on personal cycling skills results, our research shifted the attention to their children’s experience.

Researching a model for children with children can be fun. Credit: City of Turku

It was surprising that the field testing of children’s cycling simultaneously acted as an inspiring and motivating experience for them, as 87% of them felt more motivated to cycle due to the testing and the skills card distributed afterwards. What the research has failed to explore was whether the repetition of the cycling track and knowledge of the skills being monitored were responsible for such a significant increase in motivation to cycle, or whether the same impact would have occurred without the repetition or monitoring.

The research also failed to determine whether the objectively measured skill of cycling correlated with a parent’s perception of the safety of allowing their children to cycle.

In the case of a city trying to bring about change across an entire group rather than just individuals, Turku’s research needed to investigate the different levels of actors and existing structures or services, such as daycare and school personnel, sports services, and other sectors in a city organisation. Do they possess the necessary capabilities, opportunities, and motivations? Daycares and schools serve as ideal venues for levelling the playing field when it comes to children’s skills, given that the majority of children attend daycare, and education is compulsory. However, in the absence of guiding documents for teaching cycling skills or promoting sustainable mobility within these institutions, there is a need for internal motivation among the staff or, correspondingly, adequate resourcing, coordination, and planning from external sources.

Click here to read the article in its original format.

About the author:

Anna-Kaisa Montonen is a Project Coordinator for the City of Turku. She approaches the sustainable mobility scene from a background in physical activity and health promotion. Through her work, she aims to bring both carbon neutrality and citizen wellbeing to the forefront. She believes that a healthy, active lifestyle is a precursor to sustainability.