Regions Just Transition Webinar: Putting the periphery at the core

POLIS’ Just Transition Webinar x Regions moved beyond the city, to look toward how more rural areas can, and must, be served by mobility agendas.

Urban mobility is much more than transit across the metropolis. Journeys do not stop at the city limit, there is a continued to and from the periphery to the core and between cities themselves.

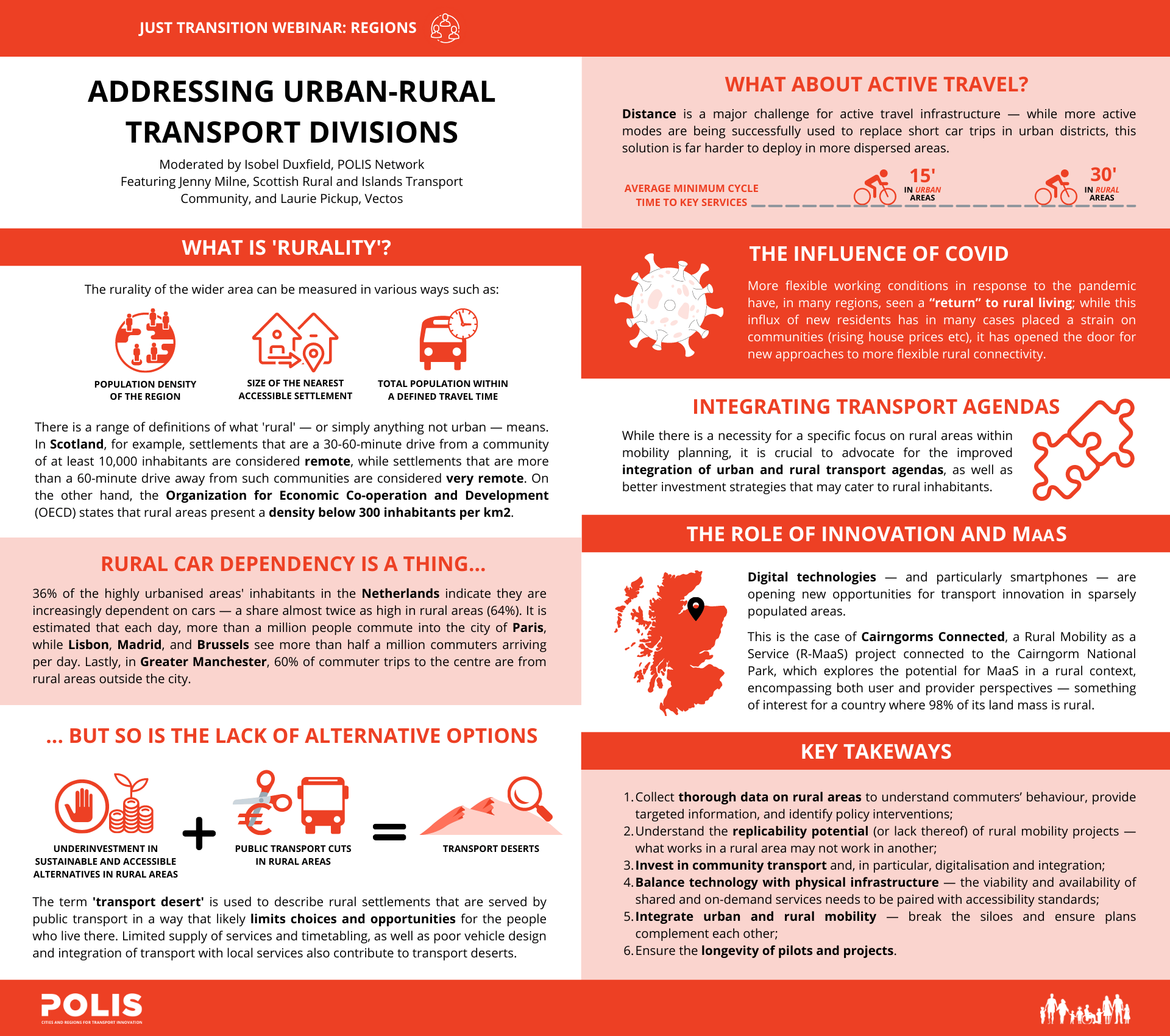

Rural areas cover more than 80 % of the total EU territory and are home to 30% of the EU population. Mobility is the glue that binds together rural communities and helps local economies flourish. However, our peri-urban and rural communities are often left behind in sustainable mobility agendas. Policy, funding, planning, and research are not given the same attention as in urban areas. We have seen a flurry of investment and political focus on reducing car dependency in cities and major urban areas with Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, School Streets and car-free cities, yet less focus on sustainable accessible, and affordable alternatives for suburban and rural areas.

The interactive webinar 'Addressing urban-rural transport divisions' examined the challenges facing practitioners and policymakers, identifying gaps in the current research and how innovative approaches can cement long-term solutions for bridging urban-rural transport divisions.

Aided by expert input from Laurie Pickup, International Director, SLR Consulting and past chair of the International Transport Forum’s global working group on Transport Innovation for the Periphery, and Jenny Milne, Founder and Director of the Scottish Rural and Islands Transport Community (SRITC) who is currently conducting a PhD on Rural MaaS, this Just Transition Webinar brought the periphery centre stage, shining a spotlight on rural mobility planning — download the PDF here.

image: Glenfinnan, Scottish Highlands, United Kingdom, Katia De Jua/Unsplash

The great divide & why rurality matters

Once we move beyond the city core, car dependency rockets. For example, Eurostat figures reveal that in Greater Manchester, the share of people using a car to get to work was 18.3 percentage points higher in the surrounding region than in the city centre (71.1% vs 52.8%).

This is underpinned by multiple, complex components, including territorial, socio-economic, and demographic factors; yet, at the heart of this division, there is a Europe-wide underinvestment in more sustainable and accessible alternatives in rural and peri-urban areas.

“In rural areas, low mobility hurts much more,” asserted Pickup. “Cities may be focused on carbon zero, and this is important to regions, but not as much as accessibility right now!”

Rural transport is a concern not just for regions, but cities too.

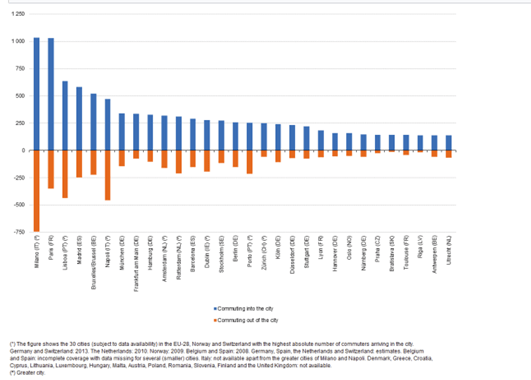

It is estimated that each day, more than a million people commute into the city of Paris, while Lisbon, Madrid and Brussels see more than half a million commuters arriving per day. In Greater Manchester, 60% of commuter trips to the centre are from rural areas outside the city- figures which have not been significantly affected by the pandemic.

Indeed, as previous POLIS Regions Working Group meetings have revealed, without channelling investment into rural areas, decarbonisation, decongestion and modal split goals everywhere are jeopardised.

The Future of Transport Outside Cities report, exposed that areas outside major cities account for over 70% of national transport emissions, paired with public transport cuts in rural areas across Europe leaving “Transport Deserts” where many are left without affordable or accessible options, action is needed — fast!

“Lack of transport hurts those in rural areas the most, we are seeing a growing interest and pressure for action at national and EU level on this, but there is still much to be done,” said Pickup.

From Catalonia’s on-demand bus services to FrankfurtReinMain’s integrated cycleway network, to Stavanger’s multi-modal integration – regions across Europe are endeavouring to enhance and expand public transport and active travel provisions. Nevertheless, there is a long way to go.

Image: Commuter flows in and out of cities, Source: Eurostat https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Flows_of_people_commuting_into_and_out_of_selected_European_cities,_2011_(%C2%B9)_(thousands)_Cities16.png

Why is there such a division?

Rural transport faces a series of critical challenges which make services both physically and economically challenging to coordinate and deliver.

In many cases, the term “Transport Desert” has been used to describe many rural settlements which are inappropriately served by public transport in a way that’s likely to limit choices and opportunities for the people who live there.

The economic case – particularly post-pandemic as transport operators struggle to recover lost revenue, is (to put it mildly) tricky. It is estimated that, globally, 85% of rural bus operators run below the break-even point. However, passenger numbers remain low; in Scotland, the number of bus journeys dropped by 65% in 2020-21 following a generally declining trend which had seen bus passenger numbers drop by 21% in the ten years leading up to 2019-20.

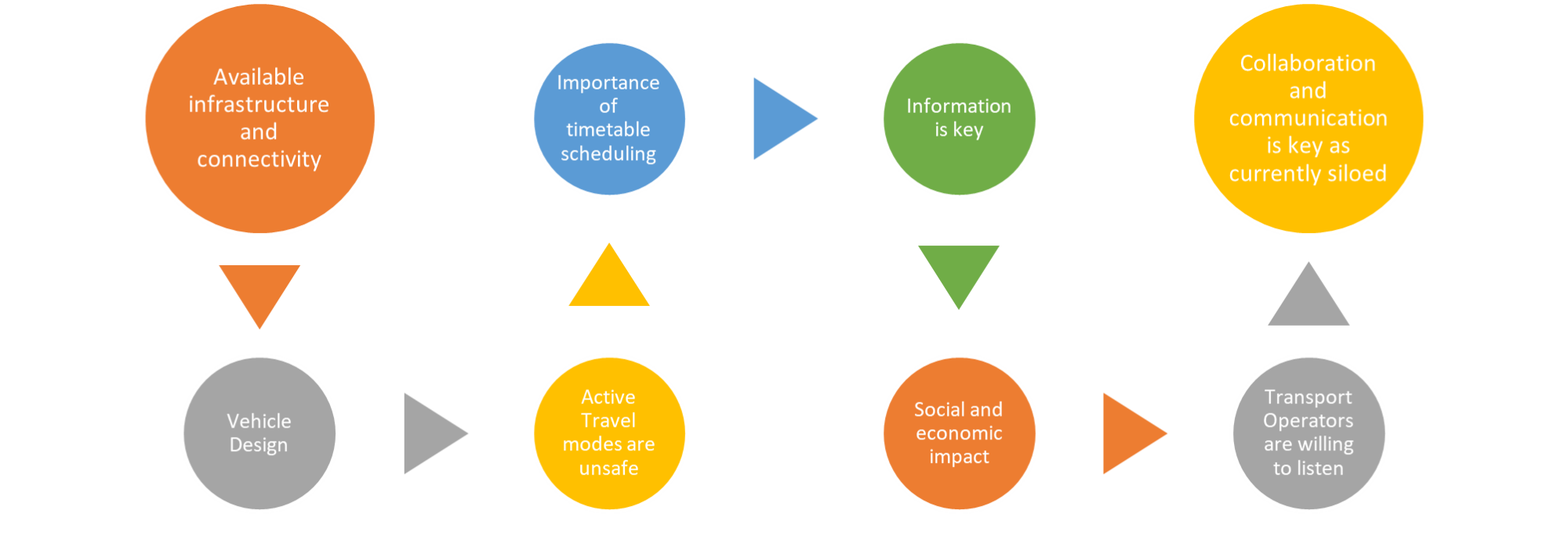

At the same time, limited supply of services, timetabling, vehicle design and poor integration of transport with local services has left many rural areas cut off- and Milne presented a range of cases from Scotland where this is causing significant challenges for locals and visitors alike.

Image: findings from SRITC research into challenges facing rural transport. Information based on research conducted with end users when talking about rural transport, and often it’s the bus people think of, but it’s not the only form of transport but it appears to underpin policy. Source: Jenny Milne

Distance is a major challenge, particularly for active travel infrastructure. With far greater distances between services, where more active modes are being successfully used to replace short car trips in urban districts, this solution is far harder to deploy in more dispersed areas. As the UK’s travel time statistics reveal, the average minimum cycle time to key services in rural areas is 30 minutes, compared to just 15 minutes in urban areas, while the average walking time in rural areas is almost 1 hour. Given that the rural population are, on average, older than in urban areas, distance and complexity of travel are key in shaping transit choices.

Yet, as Milne reminded the webinar, this is not a justification for under-investment- quite the opposite, the investment pays.

“Rural areas make up just 20% of the population, yet they contribute to 25% of the country’s GDP,” she asserted. “We need to invest in our rural areas, and fully recognise their value.”

Tackling the division: A crucial moment for action?

Jenny Milne presented the work being conducted by SRITC in creating a collective voice for rural and island communities, organisations, and businesses, building a network that can deliver a better transport future; represent the transport needs of residents to those who can facilitate change; and facilitate knowledge and best practice exchange to support innovative solutions to key transport challenges.

image: Kristin Wilson/Unsplash

She revealed how COVID-19 has undoubtedly transformed the conversation. The onset of more flexible working conditions has, in many regions, seen a “return” to rural living; while this influx of new residents has in many cases placed a strain on communities (rising house prices etc), it has opened the door for new approaches to more flexible rural connectivity.

The pandemic also opened up new channels for those working on these issues to be able to share ideas and experiences- bringing rural mobility challenges to the fore of national and international agendas.

“The explosion in digitally enabled ways of working has transformed how we can discuss these issues, the forums we can access and the exchange of ideas we, in rural areas, can have,” said Milne.

From the periphery to the core! A new language for rural mobility

As part of a more comprehensive planning process, both speakers called for a move away from the copy-and-paste approach to rural mobility so often adopted.

“It is not a competition of rural vs urban, we need to view the issues as a whole, beyond the current Siloed approach,” stated Milne.

The webinar presented a clear necessity for a specific focus on rural areas within mobility planning; however, critically, both Pickup and Milne were not advocating a bifurcation of urban and rural planning, but rather an improved integration of transport agendas, with stakeholders working together more comprehensively.

“We need a complete change of language we use,” echoed Pickup. “Away from rural areas simply being the ‘periphery’, towards independent areas with their own unique needs and demands.”

Indeed, the urgency for this is clear when examining urban mobility planning. A Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP) is a strategic plan designed to satisfy the mobility needs of people and businesses in cities and their surroundings for a better quality of life. Most- if not all- cities in Europe have one, yet, we do not treat our regions with quite the same strategic approach.

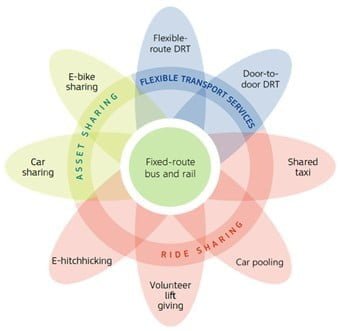

Pickup presented some key findings from the SMARTA project, which explored the key challenges of mobility in Europe’s rural areas and the existing frameworks available, before pressing for EU action.

“We looked at how we currently plan for mobility in rural areas,” described Pickup, “And the answer is… we don’t!”

Several POLIS member regions have- or are in the process of developing such plans. National Transport Authority Ireland’s (NTA) Connecting Ireland Plan seeks to bridge gaps, address uneven connectivity, and integrate timetables, while FrankfurtRheinMain’s SUMP aims to boost sustainable modes of transport up to 65% by 2030, helping to reach the EU climate goal of reducing CO2 emissions by 55% by the same year.

Yet, as Pickup noted, there is a clear necessity to create more comprehensive planning and investment strategies, which work from the bottom up, moving from the needs of rural inhabitants to the types of mobility solutions which are developed.

Image: The SMARTA Atomium, source: SMARTA Project

“There are a lot of assumptions about what rural mobility should be, and how it should be configured, often emanating from decision-makers in urban areas,” asserted Milne.

This has been a large part of the work being done at SRITC, which has been endeavouring to move rural mobility needs further up the national agenda. It submitted 6 “big asks” to the Scottish Government, which, if supported will bring much greater focus to the work that needs to be done to “level up” and decarbonise rural and island communities:

- An Integrated Rural & Islands Mobility Plan

- A Rural and Islands Transport Innovation Fund

- A Rural & Islands Transport Leadership Group

- A Rural & Islands Transport Procurement Framework

- A Sustainable Rural Transport STEM challenge

- A Rural & Islands Open Data Framework

Through these actions, SRITC seeks to secure additional support for rural mobility planning, yet retain local actors at the heart of design and decision-making.

International attention is growing

“Rural territories require policy frameworks that improve mobility in EU regions. The ‘Time to Act’ is now, through an initiative at the European policy-making level to develop a common European framework that encompasses a shared future vision for rural mobility and at the same time takes into account the emphasis on the specificities of rural areas and their populations” — SMARTA Project Final Report

From the 2021 Long term vision for Europe’s rural areas to the 2022 Rural Pact, there is growing attention from the Commission and the Parliament. Yet, while Pickup saw this as reassuring, he noted, much of this attention, and levelling up agenda, focuses largely on agriculture and other economic aspects of rural life, failing to trickle down comprehensively to rural mobility.

The SMARTA project lays out a range of pathways (Supportive, Persuasive, and Mandatory), which would see a structured set of measures for rural mobility, to be established with funding from both the EU and the Member States.

“However, continued efforts need to be underpinned by improved education and training which channels human resources towards rural mobility innovation and governance,” noted Pickup.

Moving from pilots to long-term processes

Yet, one of the biggest challenges is how to develop mobility approaches that can be sustained in the long term. Scaling up and transferring products and approaches demands political and financial viability, and too often pilot projects do not result in a wider, systematic shift in how mobility is designed and delivered.

“Post-funding and training schemes might also be needed to give project outcomes a stronger base, allowing them to be sustained over time,” said asserted one participant on the interactive board.

Indeed, this has been a challenge raised not just by POLIS’ regional members, but by small and medium-sized cities too. Maintaining momentum once a project has concluded, learning from the findings and using these for comprehensive new approaches to mobility governance is concern cities and regions are confronting. Time to work together?

Key Takeaways?

-

Collect data: Better data can help transport authorities understand commuters’ behaviour, provide targeted information and identify policy interventions. Île-de-France has developed a Regional Mobility Information Platform (PRIM) which is a one-stop shop that centralises data (60+ static datasets, 5+ API) and services around mobility to help feed the ecosystem’s MaaS applications and tools.

-

Understand replicability potential: There might be difficulty replicating successful models in other areas — successes in one area may not translate directly into another area where there are different resources and needs.

-

Invest in community transport: In Germany, the state of Baden-Württemberg has introduced several programmes to support initiatives, including digitalisation and integration. The state mobility agency (Nahverkehrsgesellschaft Baden-Württemberg, NVBW) has its competence centre for "unconventional" forms of public transport, which supports local authorities.

-

Balancing technology vs physical infrastructure: New digital technologies have propelled the availability and viability of shared and on-demand services, however, ensuring citizens have access to these is critical.

-

Break the siloes: Rural mobility does not exist in isolation from its urban counterpart! Local, national and international decision-makers need to more actively address how agendas can be harmonised and how plans can complement one another.

-

Ensure longevity: There has been a range of pilot projects including MaaS, car sharing, DRT and others which have sought to find innovative new approaches to rural mobility planning. However, the webinar revealed the focus now needs to turn to ensure findings (successes and failures) are built on and addressed comprehensively.